THE PROSPER VALLEY VIGNETTES:

Written on the Land - A Prosper Valley Cultural History

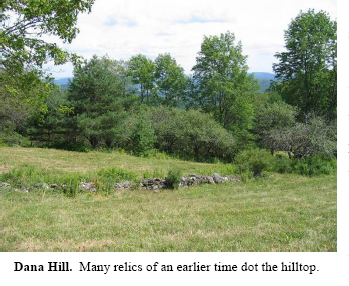

I don't know what it is I like so much about forests latticed with stonewalls. Partially, I think it's that they fuel my imagination; with the sight of one, I begin to picture how the land used to look when the stonewall was created, and I visualize how it has changed between that time and today. I had explored the entire length of the Appalachian Trail(AT) through the Prosper Valley but I kept coming back to the Dana Hill section in Woodstock and Pomfret. My first trip there had been highlighted by the discovery of giant butternut trees and fields of wildflowers and fluttering butterflies. But what really made the place special to me were the cultural relics that I gradually discovered. That hill, like dozens of others in the Valley, had a story to tell and it disclosed new clues with each passing day—some apparent, some subtle. With each discovery I understood more about the people who once lived on Dana Hill and about the relationship they had with the land.

The first indication that someone had once lived on Dana Hill was the stonewalls. They were everywhere—in the middle of fields, in the middle of forests, and on the edge between field and forest. But, if people had worked this land, where had they lived?

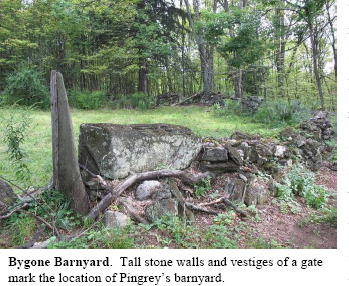

In pursuit of answers, I found myself hiking off trail on AT land, compass in hand, searching for a hole in the ground represented by a little black dot on a really old map. The map was the F.W. Beers Atlas of Windsor County and was created in 1869 (of course, the one I carried was a reproduction). Mr. Beers denoted the location of all the residences at the time of his survey with a little black dot and the name of the homeowner. So, if I could locate a black dot on the map somewhere on Dana Hill, I would have a better idea about where to look for the nearby dwelling. According to the map, "D. Pingrey" had lived on Dana Hill at the end of Austin Road and just across the Woodstock-Pomfret town line. Once I had an idea where the home site had been, I went on foot.

I arrived at an old road which, if my orienteering skills were correctly calibrated, was Austin Road. When I'd walked up the road several dozen feet I saw a gate. I went through the gate and let a tall, solid stonewall and a flat belt of ground guide me directly to the remains of a house. Within a matter of minutes I had found the relics of a barn and barnyard. Various domestic plants—lilacs, irises, apple and cedar trees—were scattered around the dooryard, indicating that people had once cared for this land.

How did they live off the land? Did Pingrey have cattle? Did he grow crops? If so, where had the fields been? To that end, I would turn to subtler clues embedded in the landscape.

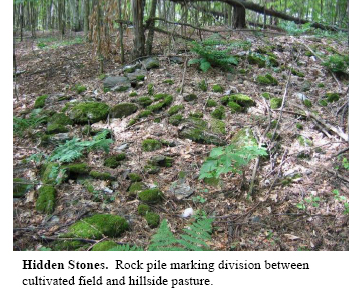

Historically, stonewalls separated parcels that were used differently, so I set out to inspect the walls lining the hills and the land they partitioned. The forest around me was a bright one, partly because it was a sunny day and partly because the stark white bark of middle-aged paper birch trees shone out from all over the steep slope. I looked down to examine the soil; I found it thin, so thin that there was exposed bedrock in many places. Paper birch is considered a pioneer species because of its ability to colonize degraded landscapes with little soil. What had caused the soil to become so thin on this hilltop? Given that the site seemed too rocky and steep to ever have been cultivated or mowed, I guessed that grazing animal hooves were the answer. I could picture a few dozen sheep or cattle grazing the steep hill, tearing soil from bedrock with each step, and creating the perfect site for paper birch seed germination. Lying in wait beneath the aging paper birch were shade-tolerant sugar maple and American beech— ready, when a birch succumbs to ice, wind or chainsaw, to take its place in the canopy. In this cycle of disturbance and change, paper birch pioneers the way for tree species that settle later and ultimately persist longer.

As the sun moved across the sky, I continued to explore the fields and forests on Dana Hill. I found rock piles where farmers had chucked rocks they moved from the plow's path and I found flat expanses of forest that had once been plowed. I found areas with several old, and hundreds of young, sugar maple trees that surely had been a sugarbush. And I found gnarly apple and pear trees where there had unquestionably been an orchard.

On my first visit to Dana Hill, the fields were full of beautiful flowers—some native, some not. Many of the non-native species, like timothy and clover, were remnants of Dana's agricultural past. By my fourth trip to Dana Hill, the fields had been mowed and the flowers replaced by unconcealed cow pies. Evidently, Dana Hill's agricultural tradition continues into the present through agricultural leases and people's lasting relationship with the land. There is something poignant about standing in a place that has been farmed for over two centuries. Legacies of the early settlement are in the stonework and the vegetation all around. Together these clues reveal a story of people who came before—a story of how their livelihood depended on the land and shaped its future. And now, as the forest slowly reclaims the borrowed stones, the stonewall is a reminder of the linkage.