People all over the world have personal connections to rocks—they collect them, carry them as "worry stones," adopt them as pets, and create altars from them. For most every individual, the sight or feel of a particular rock summons vivid memories and personal stories. For the landscape as a whole, rocks tell stories of the earth's past.

I uncovered one such story this summer in the Prosper Valley. I found rocks on hilltops and in creek beds; there were small jagged pebbles, large smooth boulders, and rocks with highways constructed through them. Some of the rocks had rough, pocked surfaces like they had been to Mars and back; others, when captured in a sunbeam, flashed thousands of small sparkles as if they held an entire night sky. This is the story these rocks tell.

Once upon a time, the location that eventually became the Prosper Valley was beneath a vast tropical sea. Shelled creatures wafted about with the ebb and flow of tides and ocean currents while trilobites—ancestors of horseshoe crabs—scuttled across the floor of the continental shelf, where the sun infused the shallow water and supported primordial plant life. In the dark, deep ocean, out of the sun's reach, little life existed. Geologists have named this ancient sea—a predecessor of the Atlantic Ocean—the Iapetus Ocean, after the titan Iapetus, father of Atlas.

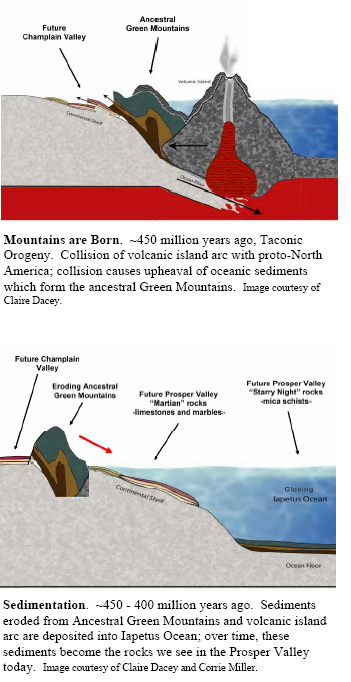

Between 500 and 225 million years ago, the continental plates—giant shifting slabs of rock that move relative to one another above a hotter, deeper region—on both sides of this vast ocean moved on a collision course toward each other. An early impact between the primitive North American continent (proto-North America), to the west, and a volcanic island chain in the ocean carried enough force to uplift an entirely new mountain chain—that which today we call the Taconic and Green Mountains.

As the plates further converged, much of the island chain and newly uplifted Green Mountains—rising along the continent's eastern margin—was eroded into the contracting Iapetus Ocean. Some of these sediments reached the dark depths of the ocean while others settled on the shallow continental shelf. It is these sediments that were thrust up during subsequent collisions and now form the bedrock that we see in the Prosper Valley. The contending plates hadn't, however, settled the score. Later collisions between proto-North America and various other landmasses forever closed the Iapetus Ocean and effectually fastened the land that is now New Hampshire and Maine onto North America.

Is it really possible that these stories are inscribed in a few rocks? One interpretation of the Prosper Valley's pocked, Martian-looking rocks is that they formed on the continental shelf of proto-North America from sediments eroded off the ancestral Green Mountains and volcanic island chain. Because they accumulated on the sunny continental shelf, these sediments were mixed with the remains of living organisms as they became rock. These rocks, therefore, have been a sort of storeroom of minerals from ancient organisms. The pocked surface results from the mineral calcite—derived from sea creatures' shells and algal mat secretions—dissolving more quickly than the other surrounding minerals. The areas on the rock's surface that were once calcite are now, after years of exposure to water, empty holes.

The sparkly Prosper Valley rocks, on the other hand, formed farther out in the Iapetus Ocean, beyond the reaches of sun-loving, calcium-secreting organisms. The sparkles emanating from the rocks are flecks of the mineral mica, which formed from clay minerals eroding off the young Green Mountains. Because of their small size, the clay particles traveled all the way into the ocean depths, past the continental shelf, before settling out in still water and becoming bottom sediments. Both of these ocean-lain sedimentary rocks, deposited on the continental shelf and in deep water, were thrust up and metamorphosed, or changed by pressure and heat, during the closure of the Iapetus. Consequently, they have a slightly different form today than upon first deposition.

The bedrock geology map of the area dubs the Prosper Valley bedrock the "Waits River formation" and describes my "Martian" rock as "impure limestone or marble weathering to a brown punky crust" and my "Starry Night" rock as "mica schist." The Waits River is a "formation" because these two rocks of different origins—one from the continental shelf, the other from deep water—exist together in jumbled layers, presumably because they were shoved together during the plate collisions. This Valley is part of a large swath of the Waits River formation that runs the length of Vermont from Canada to Massachusetts, paralleling the ancient shoreline of the Iapetus. Immediately to the west of the Prosper Valley begins the wide belt of Green Mountain metamorphosed mudstones—similar in origin to my "Starry Night" rock, but with fewer impurities and greater degrees of metamorphism. To the region's east are the granites of New Hampshire that came from volcanic activity during the closing of the Iapetus.

In all these ways and more, geological events happening millions of years ago affect our experiences in the Prosper Valley today. The thought that the shell on the back of an ancient sea creature would end up in the rocks all around us is miraculous enough. But, the fact that this little shell, now in the form of calcite in the rock, causes the Prosper Valley soils to be significantly more fertile than those to the east or west is where it gets really interesting. This interaction between the Prosper Valley's bedrock and everything atop it is where the plot thickens, so to speak, and where my tale of the Prosper Valley landscape begins.