they were delicious

so sweet

and so cold

Reading Poems

Huck Gutman

Professor of English

The University of Vermont

Section Two

You Can Read A Poem:

The Guidelines Elaborated

1.

Someone is speaking to us about something which seriously concerns her/him.

2.

The lyric poem issues from a self.

3.

That self wants to make contact.

4.

The poem always – just like a person -- has a voice, a recognizable and

unique voice.

5.

There is almost always an emotional tenor to a poem.

6.

We are all so uncomfortable with ourselves that saying something important

often requires us to be indirect.

7.

It is always better to read several poems by a poet, rather than just one;

always better to start with short poems rather than long ones.

8.

Embrace strangeness. To do this, you will have to trust your imagination.

9. Try strangeness on for size:

use yourself as a touchstone. To do this, you will have to

trust your imagination.

10. The poem is an esthetic

object: form and ‘beauty’ are always part of what is

going on in the poem.)

11. Every rule for reading poems,

including numbers 1- 10, can be discarded except this rule: LISTEN to the

poem.

1. Someone is speaking to us about something that seriously concerns her/him.

A poem is human speech about human affairs. We should always approach a poem by listening to the words in the same way as we would listen to the words of someone we care about, someone who has just said: “Wait a minute. Listen to me. What I have to say is very important to me, and I want to make sure you hear it.”

Let’s look at a small poem that, in the sixty-five years since it was written, has become more and more famous. It is by William Carlos Williams, and the title is, seemingly, a part of the poem:

This is just to say

I have eaten

the plums

that were in

the icebox

and which

you were probably

saving

for breakfast

Forgive me

they were delicious

so sweet

and so cold

The poem appears to be a note, a note explaining what the author of the note did, and why he did it. It tells us that he ate some plums, even though he knew that someone else probably had intended to eat them at a later time, because he surmised they would be – as they turned out to be – delicious, sweet, and cold. It seems abundantly clear that the writer is speaking to someone else: the words are committed to paper because the person to whom the author is speaking is not present.

Barely noticed at the time of its publication, “This is just to say” has become one of the best-known poems of the twentieth century. Remembering that a poem can be many things to many people, and even many things to one person, we may be able so see many reasons why this poem has become as famous as it has. It roots the poem in the vernacular, the language of everyday life. It raises questions about framing (is the title part of the poem?). It blurs the difference between poems and other uses of language, such as notes, thus asking that fundamental question, how are poems different from other uses of language? It insists that the accidental and momentary might be fully as worthy of preservation as high art and tempestuous passion. The poem also explores, in a very brief but telling manner, the nature of desire, which is revealed as so strong that it leads to transgression: after all, the poet’s hunger for plums was powerful enough that he knowingly violated someone else’s agenda and autonomy .

But what should concern us here, is the stark way in which “This is just to say” reveals how directly the poem speaks. Let me repeat what I said immediately before the poem:

We should approach a poem by listening to the words in the same way as we would listen to the words of someone we care about, someone who has just said: “Wait a minute. Listen to me. What I have to say is very important to me, and I want to make sure you hear it.”And this is just what Williams has done. He has something of importance to say to his wife, for she seems to be the ‘you’ he is addressing. “I have eaten the plums, I know you were saving them, I’m sorry, I couldn’t help myself. (And, by the way, did you know just how wonderful life can be when we grab hold of it: delicious, so sweet and so cold.)”

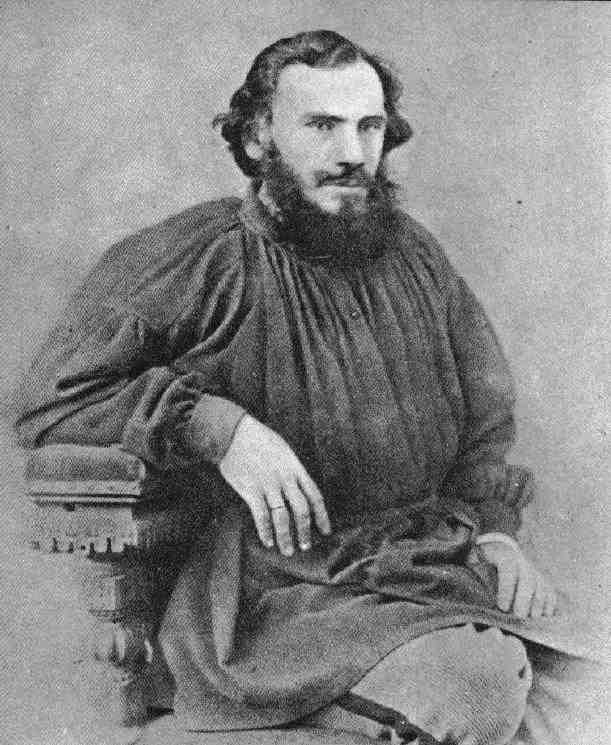

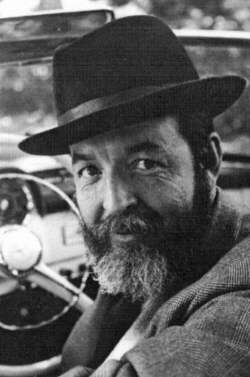

William Carlos Williams

He is telling her what he

has done. He has said he knows he has injured her. He has apologized (but

only partially: we know he would do the same thing again). And he

has told of his delight in living in a sensory world.

In short, he has had a lot to tell her – and us. This is why he has

spoken to her, in a poem.

2.

The lyric poem issues from a self.

As you read more and more poems, you will discover that the “self”

the poem issues from is sometimes fragmented, unsure of its identity, suspicious

of its own coherence. And as you read poems you will discover that

not every poem is a lyric poem, a song from the inner core. Narrative

poems tell a story; some poems describe a person other than the poet; dramatic

monologues reveal a character through his or her speech. Yet whether

the poem is a lyric or a narrative, about a person or ‘from’ a person,

we can always respond to the poem by saying, “Who is speaking to me here?”

Clearly, Williams’ “This Is Just to Say” came from a self: plum-loving, bold, transgressive, superficially apologetic.

Here is a poem written in extraordinary circumstances. Its author,

Miklos Radnoti, was a Hungarian who, after working in a forced labor camp

in 1944, was sent on a forced march with three thousand men, of whom only

a very few survived the Nazis cruel treatment. He himself died near

the

end of the march, shot by his captors and buried in a shallow mass grave.

This poem was found on his body, after the war, by his widow. The

translation is by Emery George.

Forced MarchThe man who, having collapsed, rises, takes steps, is insane;

he’ll move an ankle, a knee, an arrant mass of pain,

and take to the road again as if wings were to lift him high;

in vain the ditch will call him: he simply dare not stay;

and should you ask, why not? perhaps he’ll turn and answer:

his wife is waiting back home, and a death, one beautiful, wiser.

But see, the wretch is a fool, for over the homes, that world,

long since nothing but singed winds have been known to whirl;

his houewall lies supine; your plum tree, broken clear,

and all the nights back home horripilate with fear.

Oh, if I could believe that I haven’t merely borne

what is worthwhile, in my heart; that there is, to return, a home;

tell me it’s still there: the cool verandah, bees

of peaceful silence buzzing, while the plum jam cooled;

where over sleepy gardens summer-end peace sunbathed,

and among bow and foliage fruits were swaying naked;

and, blonde, my Fanni waited before the redwood fence,

with morning slowly tracing its shadowed reticence. . . .

But all that could still be – tonight the moon is so round!

Don’t go past me, my friend – shout! and I’ll come around!

There is no question

a ‘self’ is speaking here. That self begins by saying that to keep

marching is crazy, but if you were to ask why a man gets up after falling

(as the poet appears to have done), he’ll tell you that his wife is waiting

for him at home, and a calmer death, a death of old age, is preferable

to dying by the side of the road.

The ‘self’ in the poem says

even that hope is crazy: the world is at war, and everything is wrecked,

destroyed. Home is filled with fear, and even the plum tree is broken.

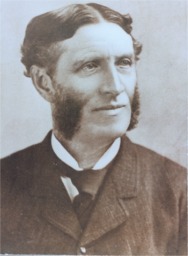

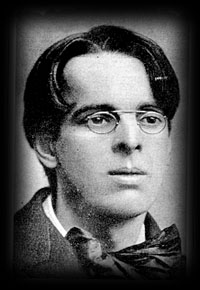

Miklos

Radnoti (1909-1944)

Miklos

Radnoti (1909-1944)

But his hope does not give

up that easily; how our ‘self’ wants to hope, to believe that home really

exists, still exists, remains somewhere for him to return to: “that there

is, to return to, a home.” An then, miraculously – tired,

collapsed, broken – the ‘slef’ imagines his home. I find it hard

to recall any lines of greater longing, of a vision of what Herman Melville

once called “domestic felicity,” than this lovely vision:

A vision at the center of which “blonde, my Fanni waited.” (With a love and longing like this, it is not had to see why she went, after the war, on the difficult mission of vinding and exhuming his body.)tell me it’s still there: the cool verandah, bees

of peaceful silence buzzing, while the plum jam cooled;

So the ‘self’ tells itself that the vision “could still be,” that home and love might be there when and if he can return. And that ‘self’ calls out to his fellow-marcher, and asks him to shout at him, to wake him from his stupor and reverie, so he can continue to march.

Pain, despair, realism, dreams, love, courage, will: a self is speaking to us in this poem. We recognize Miklos Radnoti in his words: they may be a poem, but that poem is speaking to us, from and of himself.

Now let’s turn to one of

the most famous of all American poems, Robert Frost’s 1923 lyric, “Stopping

by Woods on a Snowy Evening”. Who is speaking to us?

Whose woods these are I think I know.

His house is in the village though;

He will not see me stopping here

To watch his woods fill up with snow.My little horse must think it queer

To stop without a farmhouse near

Between the woods and frozen lake

The darkest evening of the year.He gives his harness bells a shake

To ask if there is some mistake.

The only other sound's the sweep

Of easy wind and downy flake.The woods are lovely, dark and deep.

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep,

And miles to go before I sleep.

The speaker of this poem

stops by a wintry woodland and watches snow drift down. In the act

of stopping in the middle of the cold woods, he has moved outside of normal

expectations. Even his horse “thinks” it odd to stop before he has reached

human habitation. It is a surprise to realize that, in this familiar

poem, the two middle stanzas – fully half of the poem – have to do with

the horse.

As we look more closely

at the lines, we see a conflict between social expectation, represented

by the man who owns the woods and by the horse with its sense of what is

usual and expected, and the allure of something else, represented by the

woods, the snow, the darkness, and the ‘easy wind. Is that something else

nature? beauty? reverie? lack of obligation? This speaker has a complicated

self, one that might tell all the truth but most certainly will tell it

slant (to echo Emily Dickinson), and so those questions are not easily

answered. What we do know is that there is a conflict in the heart

and mind of the speaker of the poem. He is pulled in two directions.

In the final stanza the opposition is made explicit: loveliness is in conflict (“but”) with the many promises the speaker has made, or has been pushed into making. He wants to stay, but must go on. Yet we sense that although he will continue the journey, he is not altogether sure he has made the proper choice. His repetition of the penultimate line in the final line indicates that he has, indeed, “Miles to go . . miles to go.” Those repeated miles indicate endlessness and point to boredom. “Sleep,”rest, surcease from obligation: these are a long way off, and he is doomed to slog along in the meanwhile.

The self this poem comes from is aware of inner conflicts. This self wants rest and delight, and independence from the demands of the social order. These statements are true whether the speaker of the poem is Robert Frost himself, or whether he has imagined a character who speaks to us: either way, Robert Frost directly, or Robert Frost through a surrogate, is telling us about the conflicts which rend him, and which will not be set aside until the night ends with sleep -- or even until human life terminates in the endless sleep of death.

Robert Frost

Robert Frost

3. The self which produces the poem wants to make contact.

The

need for contact is clearly expressed in a short poem of just two lines

by Walt Whitman. It is entitled “To You.”

Stranger, if you in passing meet me and desire to speak to me,

why should you not speak to me?

And why should I not speak to you?

There are many different kinds of contact.

Some poems come from the poet’s desire to make contact with a lover, a relative, a friend. We are all familiar with the notion that we can say important things through poems: the well chosen words, the brevity, the melody of the poem helps human beings express themselves – literally, since ‘express’ comes from the Latin meaning to press out -- in words.

Some poems emerge from the poet’s desire to make contact with herself by seeing her reflection or imprint in words. We do have a need to speak to ourselves, to see what we look like in a reflection: sometimes that reflection is in a mirror, sometimes in a photograph, and sometimes it is in the portrait of ourselves we make when we use words to describe what we feel within us.

Many poems arise out of the poet’s need to reach what Whitman called “you holding me now in hand,” the person who comes across the poem in a book or magazine. Poets write poems, in part, to bridge the chasm between the isolate individual self and all other persons in the world. It can be lonely, these individuated lives we live, and ephemeral, since our feelings often seem gone as soon as we have them. Poems reach out beyond the self to let other people know: who we are, what we have felt, what we share with other people in the world.

This much is always true: all poems want to make contact with the reader of the poem. Poems are actions in which the poet reaches across the gap of silence to communicate to the reader.

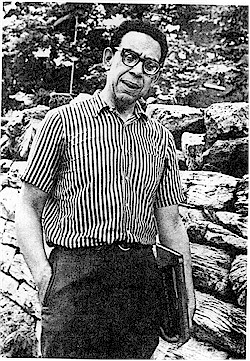

Consider this poem by the twentieth-century African-American poet Robert Hayden.

Robert Hayden

Robert Hayden

Those Winter SundaysSundays too my father got up early

and put his clothes on in the blueblack cold,

then with cracked hands that ached

from labor in the weekday weather made

banked fires blaze. No one ever thanked him.I'd wake and hear the cold splintering, breaking.

When the rooms were warm, he'd call,

and slowly I would rise and dress,

fearing the chronic angers of that house,Speaking indifferently to him,

who had driven out the cold

and polished my good shoes as well.

What did I know, what did I know

of love's austere and lonely offices?

In “Those Winter Sundays,” Robert Hayden is trying to make contact with

his father, with himself, and with us, his readers. It recollects

Hayden’s childhood, and in particular his father. It is surprising

how much we learn about familial relations from just a few remarkably well-chosen

words: “the chronic angers of that house,” “no one ever thanked him,” “speaking

indifferently to him.” It is clear that life in this family, with

this father, was difficult and strained, and that words, rather than alleviating

these difficulties, exacerbated them.

Against these generalities memory brings specific things which the young Hayden saw but did not see: the physical warmth produced by “early..cold..labor;” the emotional warmth – it takes until the last line of the poem for the poet to recognize this as “love” – which drives out the cold and polishes his shoes so he could go out into another day. The chronic angers of the house can never disappear: they were real, and they survive in memory. But as the poet recollects his childhood, he sees that love drove his father, and that his father deserved better from him than a lack of thanks and indifferent speech. Calling his father’s duties – the meaning of “offices” – austere and lonely is the son’s recognition that his father’s love has gone without response, or without love given in return for his dedication to his son. And so the poem is an apology to his father: a recognition of his father’s love, and of his own failing to as a son to recognize it.

But the poet is not speaking only to his father. There is a great poignancy to the penultimate line with its repetition, here a token of agony and self-reproach: “What did I know, what did I know…?” Here the poet is talking to himself more than to his father, expressing an agonized self-reproach at his blindness. He was young, of course, and grew up in an angry house, but in the poem Hayden is grabbing himself by the shoulders, shaking himself, saying, “You didn’t know, didn’t respond; you just took love and overlooked courage and devotion.”

The poet is also, of course, talking to us, his readers, telling us about the lonely and austere offices of parenthood, seldom understood by the young, seldom fully appreciated; and about the heroism of the parents who persist in their duties out of love, who speak the language of the heart not in words but in the difficult nurturance of everyday life.

I believe

there are always two questions we can and should ask about a poem, neither

of which is “What does this poem mean?”

(That question is part of the harmful tyranny of high school English.

It drives people away from the poem.) Here are the most basic questions

we want to ask of a poem:

· What is the person who is speaking,

who is attempting to make contact, trying to say?

· A more particular question: what are

these words saying to me?

We have looked at what Hayden is trying to say. To his father: ‘I’m sorry, I recognize now your concern and fulfilled obligation and love.’ To himself, he is saying, ‘I did not know much then; now I wish to have some of the traits of my father, to whom I owe more than I ever knew before.’ To his readers he is saying, ‘Love sometimes flows even when we perceive it not.’

What is he saying to me, to you? That is a question we each answer for ourselves. Every poem begins in silence, moves through speech and contact – and ends in a form of mute dialogue. The words which come to us from outside will, when a poem is successful and we are open to its workings, elicit something from us. Only sometimes is the final stage a dialogue in words with the poem, as when we talk about it with a friend, or in a classroom discussion. Sometimes we find outselfs in internal arguemtn with a poem. For well over a quarter of a century, W. H. Auden’s observation (in his “In Memory of William Butler Yeats”) that “poetry makes nothing happen” has risen into my consciousness every few weeks, and each time I find that my own voice rise internally to challenge Auden’s assertion. More often, the poem becomes an additional voice to the many voices that inhabit us, and we hear it speak in our minds and through our mouths. For myself, I think I can say the poem speaks to me about my relations with my own father – and to my sons. At moments I think about my father differently because Hayden’s words echo in my head. The poem modulated, and continues to modulate, into one of my own many voices: in becoming mine the contact between poet and reader is affirmed.

A generation

after Hayden, another African-American poet spoke about parent-child relations,

but from a very different perspective. Here is contemporary

poet Rita Dove describing how she feels as she nurses her daughter:

PastoralLike an otter, but warm,

she latched onto the shadowy tip

and I watched, diminished

by those amazing gulps. Finished

she let her head loll, eyes

unfocused and large: milk-drunk.I liked afterwards best, lying

outside on a quilt, her new skin

spread out like a meringue. I felt then

what a young man must feel

with his first love asleep on his breast:

desire, and the freedom to imagine it.

Rita Dove

Rita Dove

The cold chill of Hayden’s winter mornings is here nowhere in evidence: this is a sunny summer poem about a “warm” poet “lying on a quilt”. The first stanza focuses on the infant, like a sleek animal, guzzling milk, nourishing herself on what her mother willingly gives of herself. Sated, the infant slides toward sleep: Dove’s description of what has seldom been described in poetry is wonderfully precise, even to the concluding metaphor, as the child’s stuporous satisfaction is compared to the first flush of drunkenness:

FinishedIf the first stanza concentrates on the mother’s observation of her child, the second concentrates on the mother’s examination of her own feelings as the infant has finished nursing. The “new skin” is like a meringue, soft, sweet, frothy-light. Surprisingly -- poems must often surprise us so that we can see anew what we would otherwise take for granted and so not see at all -- Dove compares herself to a young man. In love and fulfilled, satisfied and drained, the desire she feels is not for something specific (the young man has, we are led to imagine, already had his sexual consummation) but for a rich and gloriously satisfying future. Having left behind the imperative of immediate need, both the young man, and by comparison Dove, are ‘free to imagine’ desire for that glorious future which they hope lies before them.

she let her head loll, eyes

unfocused and large: milk-drunk.

To whom is Dove speaking? Far less than Hayden is she speaking to another: the first stanza, and the poem itself, do capture for her infant daughter feelings which one day the daughter may wish to hear about, but that is not the primary motive driving Dove into speech. Like Hayden, she is speaking to herself, she delineates the sense of wonder and comfort she feels, and comprehends that her feelings for her infant child include a huge hopefulness about the richness which lies ahead, in time. But, quiet and personal as the poem is, and even more than Hayden, she is speaking to the reader,. ‘This is what it means to be a woman, a mother: you may not have heard this before, but I am telling you. Here is something you should know about, just as I – previously without a child, previously enmeshed in society’s images of woman and motherhood – never understood: There is a delicate yet rich wonder which suffuses parenthood.’ She tells us that to be a parent is more than to perform “love's austere and lonely offices”: it is to experience astonishment, desire, and opulent freedom.

One might claim that the poet tries to make contact because of the essential loneliness of the self. That phrase, ‘the essential loneliness of the self,’ can sound very good, particularly in those moments when we feel not merely our individuality, but our difference from and distance from other people. But both Dove and Hayden’s poems make clear that the poem makes contact (with self, other, reader) because we human beings have a deep need to comprehend: to comprehend ourselves, the world we live in, and the experiences by which self and world intersect.

The

poem is always trying to get the reader to comprehend something.

The poet makes contact to convey (to self, to another, to the reader) comprehension.

What is to be comprehended differs from poem to poem, depending on what

the poet is most concerned with at the moment of writing:

· How I [the poet] feel

· What I [the poet] see: This is

how the world looks through my eyes

· What I [the poet] am experiencing,

or have experienced

· What the world is really like,

under the veneer of the superficial, as I [the poet] perceive it

· What I [the poet] or you [the reader]

must

see if we are to be truly and fully human

· What I [the poet] could be, if

what I imagine and desire could become reality, as here in the poem my

imaginings and desires have become words

· What I [the poet] am doing, since

words not only describe the world, they act in it *1

Footnote 1 The poet contacts the reader so that an action can be performed. This dimension to language is emphasized by a philosophical movement known appropriately enough as Speech Act theory. Its basic approach can be seen if we try to ‘explain’ saying “I do” at a wedding. “I do” is an action (marrying the participant to another person who says the same thing), rather than a statement which is true or false. Speech acts can be what is called felicitous or infelicitous. For instance, Hayden’s apology to his father is felicitous because it meets our expectations for what an apology should be. Embedded in Hayden’s apology is a sense of regret and an awareness he should not have acted as he did. William Carlos Williams’ apology to his wife, on the other hand, may be infelicitious, since although he apologizes (“forgive me”) it is clear to the poet and the reader that he does not regret his actions, and would perform them again: the poem ends with the assertion that the plums were “delicious/so sweet/and so cold.” Since speaking is always ‘doing,’ when the poet makes contact he or she is doing something to or with the reader, or doing something personal, but not solitary, since the 'doing' is always before the reader's gaze.4. The poem always, just as when a person is speaking, has a voice.

Strangely, this is both one of the easiest and hardest things to understand about a poem.

The hard part is coming to an understanding of just how important voice is to the poem. I have been reading poems for forty years, and it is only in the last decade that I have recognized that it is voice, more than any other thing, which determines what is a good poem and who is a good poet. Good poets are poets whose voices are their own.

The single best determinant of a successful poet is that s/he inhabits a recognizable and unique voice. The voice in the poem is the ‘stamp’ of the personal, the impress of the poet on the words. Since in a poem someone is speaking to us – that, we recall, is the first of these guidelines – it stands to reason that the more clearly the written words resonate with the feel of an actual, definable human identity, the more we will believe that an individual human being is speaking to us. The alternative, of course, is receiving words rather than hearing them: receiving words is what we get from newspapers, junk mail, menus, contracts. (Poems can take the form of newspaper articles, shopping lists, indexes. But in being turned into poems the shopping lists – like a note on the refrigerator – are framed by the poet’s decision to use this form. It is the difference between reading a newspaper article in the daily paper, and having a good friend say to us, “Listen to this:” and then reading it to us. The voice is there, as is the sense that a particular human consciousness wants us to hear this.)

It is surprisingly difficult for most of us to understand just how important is this dimension of voice, this impress of particularity and identity on words. When most of us try to write poems, we are dominated by the voices of others, most often from the ‘tradition’ of writing poetry, and so we don’t sound nearly as individual as we do when we speak on the phone. (When we speak on the telephone, our timbre, our regional inflections, our accent on certain sounds or syllables, our use of pauses and dramatic intonations ‘color’ the words, turn the words into speech. When we write, those vocal colorings are stripped away. So the words themselves need to be colored by tone, style, use of language, and other purely verbal characteristics.) Too often when people read poems, they have a tendency to ignore the particularities of voice, and read the poem as words-on-the-page. By not listening to voice, they cut ourselves off from the poem: they don’t hear a person speaking to us, they read words on the page. Intimacy is lost, as is connectedness, contact.

There are tens of thousands of poems about the sadness of death or the power of love. The most successful poems are successful not because they tell us new things (though often they do tell us new things) but because they convince us that they come from a speaking person: someone has so effectively deployed words that we are convinced we can ‘hear’ the individual poet, and not just the conventions of language, speaking.

So once we have decided to listen to the voice of poems, hearing the poet’s voice can move from being a hard thing to do to an easy one. We are, after all, accustomed to voices. Voices are among our first experiences of the human: prior to sight, and co-equal with touch, voices reveal to each infant human being the existence of other people. That the poem, more than any other human artifact except its cousin the song, foregrounds the voice is one of the reasons poems can be so vital to our existence, and so dear to us.

When the telephone rings and I pick it up, even though I cannot see the person at the other end of the line, I can tell if my mother, my friend Bernie or Richard, my colleague Mary Lou or Patty is on the other end of the line. Within two seconds. Most of us can instantly recognize the voice of a cousin when she calls, even if we have not spoken with her for five years. What this means is we already know how to distinguish one spoken voice from another. If we pay attention to poems, we discover that they too have a voice: if we listen to them, not to what they mean but to how the words are deployed and what sorts of subjects and idiosyncratic markings of language recur, we can recognize the voice of a poet almost as readily as we can recognize the voice of a friend. So, although there are technical things that can be learned which help describe voice in a poem, things like how polysyllabic their vocabulary is, whether metrical systems are used or which or figures of speech predominate, whether the voice is inflected by irony or speaks with a seeming directness, we all have already-learned ways of recognizing the difference between one voice and another.

In reading poems, it is possible to make a person feel small and inadequate if someone demands that he or she explain why one poet sounds different from another. But each of us has enough background in distinguishing voices to be able, if we pay attention, to say, “This poet sounds different from that poet.”

Here

is a late poem by William Carlos Williams. Compare it with the poem

“Musée des Beaux Arts” by W. H. Auden in the earlier web page

: both, after all, have the same subject: Brueghel’s painting, “Landscape

with the Fall of Icarus.” Here is Williams' poem:

Landcape with the Fall of IcarusAccording to Brueghel

when Icarus fell

it was springa farmer was ploughing

his field

the whole pageantryof the year was

awake tingling

with itselfsweating in the sun

that melted

the wings' waxunsignificantly

off the coast

there wasa splash quite unnoticed

this was

Icarus drowning

Both

poems contemplate the same painting and tell us the same thing: Brueghel

painted the tragedy of Icarus as “unsignificant:” “a splash quite unnoticed

. . . the ship that must have seen something amazing … had somewhere to

get to and sailed calmly on.”

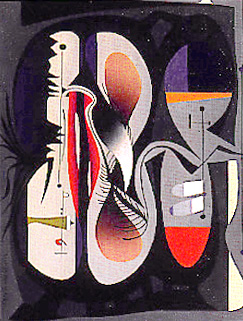

Brueghel's Painting: Landscape with the Fall of Icarus

Yet

the two poems sound very different. One is portentous, the other

quietly descriptive. One sprawls into everyday speech, the other

utters short bursts of language; this in turn means that one – Auden’s

poem – is comprised of sentences, while the other -- Williams’ poem

– is so enraptured by the painting the speaker is not even sure where his

sentences begin and end. Read the first phrases of each poem out

loud, and see how different they sound:

“About suffering they were never wrong, the Old Masters: how well they understood its human position; how it takes place while someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along…”“According to Breughel when Icarus fell it was spring a farmer was ploughing his field…”

Auden is a wordy guy, so he uses literally three times as many words as

Williams. Auden draws conclusions even as he begins to speak – we

all know people who talk like that – while Williams tries to ‘just’ retell

the story of the painting. Auden uses the world – in this case the

painting – to bolster his argument, to provide an example of what he wants

to say; Williams is so caught up in what he sees as he looks at the painting

that he feels the landscape “tingling”.

It is not a question of preferring one poem to another, although we often do make such choices, and with good reason: some poems make better, or more substantial, contact with us than others. (As for me, I love both poems: I love Auden’s willingness to summarize, the way in which his portentousness is balanced by his humor and his love of the painting with its “exquisite delicate ship;” and I love Williams’ direct response, unmediated by punctuation: the way the painting reappears in front of us on the page, transformed into language.)

Here

is a poem that has recently become a favorite of mine. Its subject

is outrageous, the events it recounts literally impossible. But the

voice of the poet is captivating – angry and petulant, astonished, friendly,

informal, theatrical, bombastic – yet the poet uses an everyday manner

of address to make the unbelievable, believable. That voice, complex

and yet direct, seduces me into accepting the outrageous events it tells

me. I love the poem as much, I think, as the poet must have loved

writing it. Its author is Vladimir Mayakovsky, a Russian who wrote

in the second and third decades of the twentieth century. At the

time he wrote this, a couple of years after the Russian Revolution – this

is the only fact you will need, for the poem is so full of its vibrant,

preposterous, enchanting voice that it needs no help from me to allow you

to ‘hear’ Mayakovsky speaking – the poet was living in a summer retreat,

making posters to for the Russian Telegraph Agency, Rosta.

The translation is by Max Hayward and George Reavey:

Vladimir

Mayakovsky

Vladimir

Mayakovsky

What can one say after reading this poem? We can only repeat the wonderful words spoken by this idiosyncratic and wonderful voice: “Always to shine, to shine everywhere, to shine – and to hell with everything else!” I think if we heard Maykovsky’s voice on our mental telephone a year or two from now, we would recognize it instantly. That’s how strong voice is, and how deep our recognition of it.An Extraordinary Adventure Which Befell Vladimir Mayakovksy In A Summer Cottage(Pushkino, Akula’s Mount, Rumyantsev Cottage, 27 versts on th Yaroslav Railway.)

A hundred and forty suns in one sunset blazed,

and summer rolled into July;

it was so hot,

the heat swam in a haze—

and this was in the country.

Pushkino, a hillock, had for hump

Akula, a large hill,

and at the hill’s foot

a village stood—

crooked with the crust of roofs.

Beyond the village

gaped a hole

and into that hole, most likely,

the sun sank down each time,

faithfully and slowly.

And next morning,

to flood the world

anew,

the sun would rise all scarlet.

Day after day

this very thing

began

to rouse in me

great anger.

And flying into such a rage one day

that all things paled with fear,

I yelled at the sun point-blank:

“Get down!

Stop crawling into that hellhole!”

At the sun I yelled:

“You shiftless lump!

You’re caressed by the clouds,

while here—winter and summer—

I must sit and draw these posters!”

I yelled at the sun again:

“Wait now!

Listen, goldbrow,

instead of going down,

why not come down to tea

with me!”

What have I done!

I’m finished!

Toward me, of his own good will,

himself,

spreading his beaming steps,

the sun strode across the field.

I tried to hide my fear,

and beat it backwards.

His eyes were in the garden now.

Then he passed through the garden.

His sun’s mass pressing

through the windows,

doors,

and crannies;

in he rolled;

drawing a breath,

he spoke deep bass:

“For the first time since creation,

I drive the fires back.

You called me?

Give me tea, poet,

spread out, spread out the jam!”

Tears gathered in my eyes—

the heat was maddening,

but pointing to the samovar

I said to him:

“Well, sit down then,

luminary!”

The devil had prompted my insolence

to shout at him,

confused—

I sat on the edge of a bench;

I was afraid of worse!

But, from the sun, a strange radiance

streamed,

and forgetting

all formalities,

I sat chatting

with the luminary more freely.

Of this

and that I talked,

and of how I was swallowed up by Rosta,

but the sun, he says:

All right,

don’t worry,

look at things more simply!

And do you think

I find it easy

to shine?

Just try it, if you will!—

You move along,

since move you must;

you move—and shine your eyes out!”

We gossiped thus till dark—

Till former night, I mean.

For what darkness was there here?

We warmed up

to each other

and very soon,

openly displaying friendship,

I slapped him on the back.

The sun responded!

“You and I,

my comrade, are quite a pair!

Let’s go, my poet,

let’s dawn

and sing

in a gray tattered world.

I shall pour forth my sun,

and you—your own,

in verse.”

A wall of shadows,

a jail of nights

fell under the double-barreled suns.

A commotion of verse and light—

shine all your worth!

Drowsy and dull,

one tired,

wanting to stretch out

for the night.

Suddenly—I

shone in all my might,

and morning ran its round.

Always to shine,

to shine everywhere,

to the very deeps of the last days,

to shine—

and to hell with everything else!

That is my motto—

and the sun’s!

5. Emotion is almost always a major part of a poem.

Our emotions are never entirely divorced either from what we experience or from what we say, and so it should come as no surprise that there is an emotional tenor to every poem.

Lyric poetry exists precisely in order to investigate emotion. Just as the biology laboratory is the place in which we expect the physical structure of vertebrates to be examined, just as the psychology lab or the psychiatric clinic is where we expect a clinical investigation of human behavior, so the poem is the place in which we expect, or ought to expect, our own emotions to be examined. Since the lyric poem issues from a self and is always concerned with emotion, it follows that the lyric poem is the domain in which our own feelings can best be encountered and explored. The poem exists to reveal us to ourselves, as well as to reveal the interior selfhood of another person to us. By examining the poem closely, then, we can examine ourselves: who we are, who we might be, what we might expect of the variety of feelings which course through us at every moment.

As all poems have an emotional tenor, it is difficult to decide just which poem might be a particularly good example of the emotional dimension to a poem. Let’s look at a poem more difficult, on its surface, than any of the poems we have read so far. This poem is called “Large Red Man Reading,” and it was published by the American poet Wallace Stevens in 1950, near the end of his long and rich career as a poet. The poem imagines – and a considerable stretch of the imagination is needed – that the dead return to earth, as ghosts, to listen to a man reading from a book of poems.

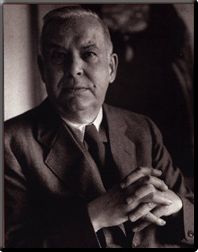

Wallace Stevens

Wallace Stevens

Although Stevens is usually regarded as one of the most philosophical of

poets, this poem, while philosophical, is about the everyday life we inhabit,

and how rich it is, how particularly rich in feeling. The poem is

at once about feeling, as you shall shortly see, and an expression of feeling:

the feeling it expresses is the poet’s love for the things we encounter

each day as we live in the world, the world which is revealed to us by

our feelings for and about it; and of his love of the poems which capture

those feelings so astonishingly vibrantly.

In the first stanza of the poem, the ghosts return to earth to “hear” the phrases that the man reads aloud from “great blue tabulae,” a mythic phrase suggests turns the pages of a book are akin to the tablets on which the divine law was handed to Moses. The ghosts who had expected more of death have returned to encounter “what they had lacked,” as the ending of the poem asserts.Large Red Man ReadingThere were ghosts that returned to earth to hear his phrases,

As he sat there reading, aloud, the great blue tabulae.

They were those from the wilderness of stars that had expected more.There were those that returned to hear him read from the poem of life,

Of the pans above the stove, the pots on the table, the tulips among them.

They were those that would have wept to step barefoot into reality,That would have wept and been happy, have shivered in the frost

And cried out to feel it again, have run fingers over leaves

And against the most coiled thorn, have seized on what was uglyAnd laughed, as he sat there reading, from out of the purple tabulae,

The outlines of being and its expressings, the syllables of its law:

Poesis, poesis, the literal characters, the vatic lines,Which in those ears and in those thin, those spended hearts,

Took on color, took on shape and the size of things as they are

And spoke the feeling for them, which was what they had lacked.

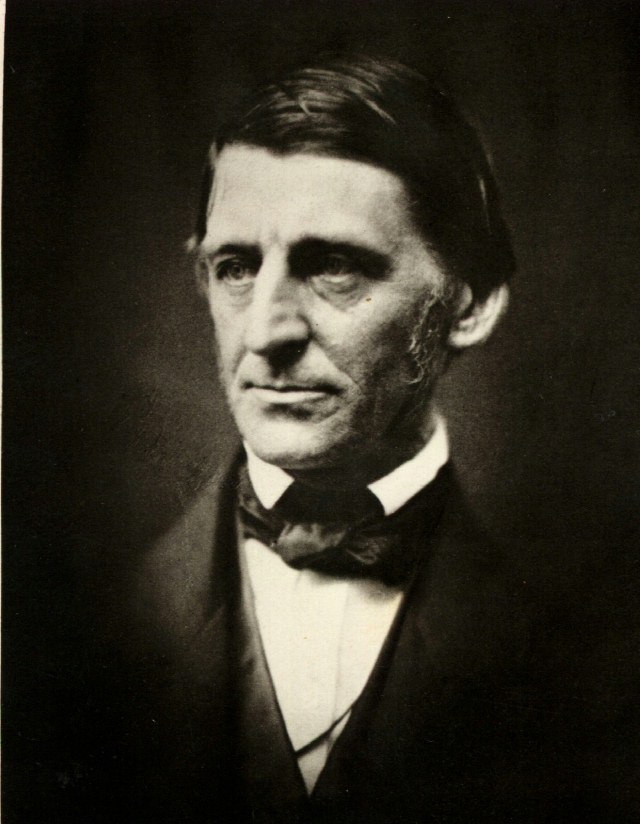

In the second stanza

Stevens identifies the book from which the large red man reads: it is the

poem of life, and it sounds surprisingly like the poem that Ralph Waldo

Emerson had insisted that American poets should write in a famous speech

made 114 years earlier, “The American Scholar:”

What would we really know the meaning of? The meal in the firkin; the milk in the pan; the ballad in the street; the news of the boat; the glance of the eye; the form and the gait of the body . . .Ralph Waldo Emerson

Like Emerson, the ghosts want “the pans above the stove, the pots on the table, the tulips among them.” So strong is their need for the physical presence of actuality that “they would have wept to step barefoot into reality.” They long for the feel of things, for shivering at frost and crying in pain at the thorn of a rose; even the ugly, just by its physical presence, would make them laugh at the delight of existing in a sensory world, a world in which one feels things, once again.

The poem, according to Stevens, is the place where being is expressed (stated, pressed forth as wine is expressed from grapes or oil from olives); in the poem existence is shaped (outlines, law) into syllables. Stunningly, the poem reverts to Greek: poesis, poesis, it cries out. The Greek word reveals how close is the relation between making and poetry, since the linguistic derivation of ‘poem’ is the Greek verb poiein, to make. In Greek, poesis means both ‘to make’ and ‘poetry.’ The “literal characters” of the poem -- its letters and syllables – are vatic, or prophetic; and what they prophesy is the real world and not the world of spirit: the pans and pots and flowers, not the domain of soul which, presumably, is occupied by the ghosts.

![]()

![]()

What the ghosts lack is “the shape and size of things as they are.” How often do we take for granted, the poem cries out with emotion, the wonders which are all around us: stoves, tulips, thorns, the miracle of words? How often do we ignore the feelings which “color” everything we experience, those feelings which give to things their dimension? We feel our way through the world, using not just our senses but our emotional responses.

Stevens tells us many things in this poem of ghosts revisiting the world

to listen to a large red man read from blue/purple pages. First,

he tells us that the things in this physical world, the pots and tulips

and thorns and sounds, are important,. Second, he tells us

that nothing is as real as the way we feel our existence. Third,

he tells us that poems are the proper province for the expression and discovery

of feelings. And, finally, he tells us that he loves the world, loves

the feelings one can have in the world, and loves the poems where being

is outlined and expressed. This poem is far more than a poem about

philosophy: it is a love poem.

Each of the lines in the poem “took on [the] color” of Stevens’ love for

a world in which things, feelings, and poems exist.

6. We human beings are more uncomfortable with ourselves and with our fellow human creatures than we like to acknowledge, and in consequence poems are more indirect that we might expect them to be.

That is what Emily Dickinson asserted in “We introduce ourselves,” and I believe she is right in that assertion. We would like to hang loose and be honest, be it with others or ourselves, but we find this more difficult than we wish. Partly, it has to do with “Etiquettes, embarrassments, and awes.” Partly, our difficulty has to do with language itself: words are not transparent, and syntax is not infinitely subtle. We each know that it is sometimes difficult to ‘put into words’ what we are thinking, feeling, or want to say. This, after all, is why cultures so often revere poets, for poets do what Whitman claimed for himself: “I act as the tongue of you,/ Tied in your mouth, in mine it begins to be loosen’d.”

Here is a poem about us speaking the truth, which is what poems try to do, by Emily Dickinson. Let’s pay particular attention to the surprising advice she gives in the first line, for the remainder of the poem elaborates on this advice.

Tell all the Truth but tell it Slant –

Success in Circuit lies

Too bright for our infirm Delight

The Truth’s superb surpriseAs Lightning to the Children ease

With explanation kind

The Truth must dazzle gradually

Or every man be blind – [Written around 1868, first published in 1945]

Emily Dickinson

Dickinson's counsel sounds

strange at first, but the more one ponders the opening line the more apt

it seems. We quickly discover that underlying the poem is a recognition

of terror. Terror is, if we search our own memories or our experiences

with children, what kids feel when a storm brings lightning and thunder.

And that terror needs to be explained so that the child can “gradually”

grow used to the explosive power of storms. The poem’s surface suggests

“superb” brightness and “dazzle.” But then, in this poem, the positive

terms such as bright, superb, delight, kind, dazzle, are all circuitous

ways of saying that the truth is so startling and dangerous it can lead

to blindness.

So Dickinson recognizes that we cannot just tell the truth: we always, if that truth is to be heard, have to sneak up on it. In more discursive forms than a poem like this, speech can begin with introductions, preambles, prologues. But the poem is economical: its power derives from saying more than is usually said in fewer words than are usually used. That economy – we will discuss this later – and the seemingly contradictory need to approach truth circuitously mean that poems often use devices to sneak up on their subjects, to come on them aslant. Metaphor, simile, exaggeration, irony, all of these are called figures of speech, or tropes. Poets play little games so they can get said those things they want to say. These games are ways of telling the truth, but telling it slant.

In the public world, the world E. M. Forster once famously called the world of ‘telegrams and anger,’ people often say that we must be direct, that there can be no shilly-shallying around, that we should say what we mean. But I don’t think the social world, public or private, works quite that way.

Imagine for a moment someone walking up to you and saying, ‘I love poetry.’ You’d think he was either pompous, or crazy. Imagine someone you know saying, ‘I have known you for several weeks. I love you.’ I’m not sure you would think he or she was crazy or pompous, but your response would not be the straightforward response the person who declared his love expected. We want to be wooed; we need decoration, flowers, song, a carefully prepared intensity, when someone speaks to us of love. We don’t really want flat statement, and are sometimes frightened by it. (We do want the words ‘I love you’ said, it is just that they need to be said as part of the game of love, and not without preamble or context.)

One more supposition. Imagine a friend walking up to you and saying, ‘You are going to die.’ And then pausing ominously before continuing, ‘It could be in many years, but it could also be tomorrow.’ The statement is no doubt true, but we don’t want to hear it. Not phrased that way, bluntly, directly. We can take the truth, Dickinson says, but only if we are eased into it. We must tell the truth slant, in a roundabout way.

Here is the strange paradox of language: If we want to use language effectively, then we must use a certain amount of indirectness. It is not merely human psychology which requires indirection. Language itself is at best a remarkably supple but still awkward instrument: it is not a perfect match for the world. Turning the simplest experiences into words can be difficult; how much more problematic, then, trying to deal with ephemeral perceptions or with feelings so deep we cannot plumb them ourselves.

On the website which precedes this, I claimed that the poetry of T. S. Eliot was one of the reasons fewer people read poetry today than did in the last century. In the second decade of the twentieth century Eliot had a number of problems. He had an unsatisfying and perhaps almost non-existent sex life. He got married to a woman who rather promptly had a nervous breakdown, partly caused by her proximity to Eliot. He had to deal with the arrival of his adored mother, who crossed the ocean to visit him in England, a circumstance complicated by his need to prevent her from seeing how desperately unhappy his life had become. Out of this matrix he made an immensely difficult poem, The Waste Land. (If a poll of twentieth century writers and scholars were taken, asking ‘What is the most important poem of the twentieth century’ I have no doubt that The Waste Land would win by a landslide.) (if you want to read The Waste Land, a long but rewarding process, you can find it at: The Waste Land.)

The Waste Land drove readers crazy. Some readers responded to the great emotional power which had forced the poem into being. But most readers were turned off by its range of literary allusions (many addressed in footnotes supplied by Eliot himself), its dependence on a vast knowledge of anthropology and Eastern religion and philosophy, its brilliant ventriloquism of many voices. They did not want to push through (and who could blame them!) the many levels of difficulty, the many diversions and indirections, the many poses and masks, which Eliot had adopted “to tell all the truth / [but] tell it slant” not only to others, but to himself. The poem is both an escape from the truth, and a bold attempt to tell it in the only way the uptight but brilliant young poet could manage to tell it. He not only found “success in circuit” by taking such a roundabout way of revealing himself that most readers of the poem never even knew he was the subject of his poem, he was pretty successful in hiding that truth from himself. Even Eliot came to believe the poem was about Western history and the decline of modern society and not, primarily, about himself.

Walt Whitman comes on to many readers as one of the most honest poets who ever wrote.

Walt Whitman

Walt Whitman

That’s the way he likes to present himself most of the time, and he’s so effective that we tend to believe him. Yet Whitman understood, all too well, how deeply buried are the truths about himself the poet needs to put into words, but fears to make public. Here is a poem seemingly about biographies, though it is actually – the truth in this poem is approached indirectly – about his own reticence, the hiding and withdrawal which take place underneath that widely-recognized openness:

When I Read the BookWhen I read the book, the biography famous,

And is this then (said I) what the author calls a man’s life?

And so will some one when I am dead and gone write my life?

(As if any man really knew aught of my life,

Why even I myself I often think know little or nothing of my real life,

Only a few hints, a few diffused faint clews and indirections

I seek for my own use to trace out here.)

This is the domain of

the poem: only a few hints, a few diffused faint clues and indirections.

The truth will be told, but not directly.

The reason I went on at length about Eliot a page

back, though, was to partially rehabilitate him. In a magnificent

passage, he helps us to understand that it is not only our difficulty in

introducing ourselves to ourselves that makes indirection the province

of the poem, but also our inability to make language do precisely what

we want it to do. In his late poem “East Coker” from

the book called Four Quartets, Eliot wrote about just how difficult it

is to put one’s feelings into words. I think no one every captured

that difficulty better:

Trying to learn to use words[:] every attempt

Is wholly new start, and a different kind of failure

Because one has only learnt to get the better of words

For the thing one no longer has to say, or the way in which

One is no longer disposed to say it. And so each venture

Is a new beginning, a raid on the inarticulate

With shabby equipment always deteriorating

In the general mess of imprecision of feeling,

Undisciplined squads of emotion. And what there is to conquer

By strength and submission, has already been discovered

Once or twice, or several times, by men whom one cannot hope

To emulate – but there is no competition –

There is only the fight to recover what has been lost

And found and lost again and again: and now, under conditions

That seem unpropitious. But perhaps neither gain nor loss.

For us, there is only the trying. The rest is not our business.

T. S. Eliot, Painted by poet Wyndham Lewis. In the Durban Art Gallery, RSA

We try, through poems,

to “get said what must be said” (the phrase comes from William Carlos Williams).

But saying precisely what we needs to be said is difficult. The poet

writing the poem is, in Eliot’s military terminology, making “a raid on

the inarticulate.” Eliot was writing in the period after the First

World War, and although he was never a soldier he uses the extraordinarily

difficult and ultimately senseless experience of trench warfare as a metaphor

for the difficulty of writing. It is as if we go to war on our own

reality to compel it to shape itself into words, but we have shabby

weapons, a mess of a battleground, and undisciplined and disorderly allies.

No wonder the battle is fought “under conditions that seem unpropitious!”

Eliot is being particularly modernist when he says each raid on the inarticulate is “a wholly new start,” adhering to his friend Ezra Pound’s artistic credo: “Make it new!” But Eliot is right nevertheless, because each poet must begin anew: words from the past belong to the past, and the poet’s need for expression comes from his own existence at the particular moment in which he feels and experiences whatever it is that demands to be put into words. Even his own previous efforts are of little help – “One has only learnt to get the better of words for the thing one no longer has to say, or the way in which one is no longer disposed to say it” -- because past competencies are linked to old conditions, while what the poet is feeling now requires new language and new forms.

Worse, the modern poet has the sense that what she may find at the end of this battle has already been found by other writers, his predecessors, giants like William Shakespeare, John Donne, or Emily Dickinson. The modern poet cannot compete with them, and does not even try, although here Eliot may be disingenuous: He tried to be a great poet, and so for that matter did Shakespeare, Donne and Dickinson. Nonetheless, each raid on the articulate is a new attempt to do what has been done before, and each momentary recovery of lost ground is doomed to failure as time moves relentlessly onward. “Perhaps [there is] neither gain nor loss. For us, there is only the trying. The rest is not our business.”

In this “general mess

of imprecision of feeling” where the poet works with “shabby equipment,”

the poem will labor mightily to speak to us. But it will not be able

to say, plainly and forthrightly, what it means. Our struggle with

language means that even when we try to “tell all the truth,” we must,

like Emily Dickinson, “tell it slant.”

7.

It is always better to read several poems by a poet, rather than just one.

At some point, hopefully fairly soon, you will move beyond this guided introduction to reading poetry entirely on your own. If there is one point at which your budding confidence that you can read poems will get tested, it is that moment when you open a book of poems and are overwhelmed by how many there are to choose from, how unfamiliar they all look, and how difficult it is to understand the first new poem you begin to read.

Don’t worry. You don’t have to read the poem if it seems to make no sense. There is nothing wrong with trying another, and another.

When we go into a clothing store, we look over the rack, or several racks. We know we don’t have to buy the first item we see, and we also know that if we look around no one will insist we leave the store. When we go to the supermarket we look around to see which fruits and vegetables appear freshest and most appealing, or are selling at the best price. We don’t automatically buy iceberg lettuce because that is the first item in the vegetable section, or artichokes, arugula or asparagus because they are first alphabetically.

Let’s pursue the food analogy in another direction, not with a store but a restaurant. Just as food is sustenance, so is human communication. But not every dish on a menu is equally appetizing. Read poems as you would read a menu: think about a number of different items as your eye moves over them, and decide which is most appealing, which you might like to taste. Or, closer to home, read poems as you might read magazine articles: try reading, and if the words don’t grab you, pass the poem by and try another. Few of us read Newsweek or Vogue, or a newspaper for that matter, straight through. We browse, and pay attention when we come across something that interests us. Poems are sustenance, but they are not medicine: you don’t need to ingest if you find a poem which is not to your taste!

A corollary of this is based

on the menu experience as well. Just as in a new restaurant – let’s

say, the first Thai restaurant you ever went to – you can select one or

another dish from the menu but eventually have to order something

or

you will go hungry, so in a selection of poems you eventually need to try

one poem, reading it all the way through, and reading it carefully to see

what sort of ‘flavor’ and ‘nourishment’ it provides. The first time

you tasted Thai food, it may not have appealed to you. But tastes

are partly learned: the best example of which this is that people in Thailand

like Thai food, in large part because they have eaten it all their lives.

Poems, as we will see when we get to the next guideline, stretch us to

encounter new things and, and Eliot reminded us a few clicks back, poems

also stretch language so that it can perform new tasks in new ways.

So at some point you need to choose a poem and work on figuring out what

the poet is saying to you. (If after working on a poem you find you

don’t like what it says or how it is saying it, fine. You can turn

to another poet. After all, if you found Thai food too spicy or too

strange you wouldn’t go back to a Thai restaurant the next night: you’d

pick an Italian restaurant or a steak house.)

One of the great truths about poetry, and literature in general, is embodied in a well-know phrase out of popular culture: ‘different strokes for different folks.’ Hart Crane is a fine and important American poet. I can’t read him. Edgar Allen Poe wowed the major French poets of the later nineteenth century, and has an enduring place in American literary history. I don’t like his poems. There is nothing wrong with Crane or Poe, but there is nothing wrong with me, either. We each have needs and tastes that are our own, and sometimes no matter how high the praise for Thai Masaman curry or French foie gras or Russian caviar, we just don’t like them. Poetry, in defiance of what some high school teachers and college professors tell us, is the same way. We don’t all have the same appetites or the same friends: why should we all have to like the same poems?

Don’t get me wrong. After reading around in a book of poems, checking out a number of them, you have to choose one and read it carefully. (Just reading around by itself is important. We can get an idea of the lay of the land by strolling through the landscape, and similarly by wandering through poems we can get a general – and sometimes capacious – sense of what is there for us to explore at greater length. And since, as we have seen, voice is the central feature of the poem, listening to a poet for a time, and listening to her speak in a variety of different situations, is a good way to become acquainted with her voice. That’s how things work in everyday life: encountering the voice is poems is not very different.) But, having read a poem or two carefully, if you don’t like what you have encountered: Trust yourself. That was what Emerson said in 1841. “Trust thyself: every heart vibrates to that iron string.” He concluded, and it is just this I am trying to tell you when I say that there will be highly-regarded poems you don’t like, “I suppose no man can violate his nature.”

The three great enemies of poetry are the notion that finding the meaning of a poem is the most important thing we can do with a poem, the notion that appreciating the craft of a poem is the most important thing we can do with a poem, and the notion that poems are like medicine, that because they are good for us we have to swallow them whether we like their taste or not. Far better to listen to the voice of the poet speaking, and to trust yourself to respond to the poem.

Since this guideline has

to do with how to approach a new poet, here is a corollary. Go

for short poems. I have a sneaking suspicion Edgar Allan

Poe was right when he said in a magazine article (which he wrote while

hard-strapped for cash):

If any literary work is too long to be read at one sitting, we must be content to dispense with the immensely important effect derivable from unity of impression—for, if two sittings be required, the affairs of the world interfere, and every thing like totality is at once destroyed…. It appears evident, then, that there is a distinct limit, as regards length, to all works of literary art—the limit of a single sitting….Holding in view these considerations, as well as that degree of excitement which I deemed not above the popular, while not below the critical, taste, I reached at once what I conceived the proper length for my intended poem—a length of about one hundred lines.

Edgar

Allen Poe [Click for "The

Raven"]

Edgar

Allen Poe [Click for "The

Raven"]

Poe was writing about how he composed his poem “The Raven,” and we may take this passage, and the whole essay it comes from, “Philosophy of Composition,” as tongue in cheek, mocking his own sincerity as a poet. But Poe (even if I don’t respond well to his poetry) was a brilliant man, and even in his mockery and commercialism he tells us the truth. Shorter poems have a coherent intensity that ebbs and flows in longer poems.

Shorter poems are also shorter. Just as when you are in a Thai restaurant for the first time, you will feel less trapped with something you don’t like if you order an appetizer or a small portion rather than a large dish, so with poems. Small or short is not necessarily better than large or long, but if you have to swallow something, short is easier to manage than a huge amount of reading. With a short poem – and I am more radical than Poe, since for me short is twenty lines or less – the reading is over quick; if you don’t like what you read, it is only minute until you finish up and can turn the page. One of the things which leads to a distaste for of poetry is the sense of obligation, of having to flog on through endless pages of words. So when you encounter a new poet, a new book of poems: browse, read short poems, find one or two you like, read them more carefully. And then, if you don’t like what you have listened to, don’t feel obliged. Put the book aside and turn to something else. (If you were partly intrigued and partly turned off, put the book aside as well. You can always come back to it later.)

Here is a poem by Wallace

Stevens which I have quoted to myself for many years. It is a wonderful

example of browsing through poems. Each time I read the poem I browse

through the first three stanzas, and then happily, almost in a trance,

recite to myself the mischievous and fun-filled final two stanzas.

This is a poem which I have never really read, even though I must have

browsed through it two hundred times over the course of thirty years.

But it doesn’t matter, at least to me, that I don’t know the ‘meaning’

of the poem, that I haven’t really figured out how its parts relate to

one another. What I like, and the poem is about exactly this, the

process of liking, is what it playfully tells us in the final five lines.

Table TalkGranted, we die for good.

Life, then, is largely a thing

Of happens to like, not should.And that, too, granted, why

Do I happen to like red bush,

Gray grass and green-gray sky?What else remains? But red,

Gray, green, why those of all?

That is not what I said:Not those of all. But those.

One likes what one happens to like.

One likes the way red grows.It cannot matter at all.

Happens to like is one

Of the ways things happen to fall.

Wallace Stevens and his wife Elsie, who he happened to like and then happened to like not as much

Every poem, every poem, has something which is strange, new, difficult, disquieting, perplexing. Poems should, as I have just finished suggesting, be accessible to us; at the same time, we need to be prepared to encounter strangeness in a poem. Sometimes it will be the whole poem itself which will seem strange or unfamiliar; at other times the poem will make sense until we begin to think about it more carefully, and then we will realize that something or other in the poem is not fully explicable.

A short while ago I used the example of a Thai restaurant to illuminate a point about how we might approach a new poet and her poems. Here is one last example drawn from this metaphor. (Truly, this is the last time!) Thai cooking, just as French cooking or Mexican cooking or Louisiana cooking, requires skill and effort, and the best Thai or French or Louisiana cooks are those who have mastered often-complex techniques and comprehended the history and diversity of their cuisine. We can enjoy Thai or Mexican cooking without understanding much about the traditions and procedures of those ways of cooking, but the more we pay attention to the ingredients in a dish, the more we know about the ways of cooking the dishes we eat, the more complex and rich our enjoyment can become. It is the same with poetry. We can get a great deal from the voices which speak to us in poems, but if we are willing to work at listening closely to those voices, listening really closely, new dimensions of enjoyment and reward are open to us.

So, although I think readers of poems should always be encouraged, I am going to venture into difficult territory for a few pages. Bear with me.

Poems are always strange because of what they do. Poems use language to different purposes than newspapers, television advertisements, political slogans, even everyday conversations. I’d like to propose four dimensions to poems which underlie the odd guideline we are exploring here: Every poem has something about it which is strange.

The first flows from something we have already explored, in elucidating guideline six: We human beings are more uncomfortable with ourselves and with our fellow human creatures than we like to acknowledge. Because we are awkward with ourselves we speak indirectly; because we find language tough to manipulate, especially when it comes to putting the evanescent or the complex or the profound into words, poems will often be more difficult to read than traffic signs. When a hexagonal red sign says “STOP” it is supposed to mean only one thing, and to mean it clearly: ‘Do not drive your car through this intersection without stopping and looking around. Stop here because the law requires it; stop because your life may, literally, depend upon it.’ But poems are filled with “etiquettes/embarrassments/and awes,” and are not like STOP signs. So we already have come upon one reason why poems can appear strange to us. There is much about them that is hidden, contorted, or difficult to put into words.

The second dimension to poems which accounts for their always being strange to us is that the poem comes from another person. The poem is a voice, but although it may serve as a surrogate for our own (“I act as the tongue of you/Tied in your mouth, in mine it begins to be loosen’d”), the voice of the poem is not our own. I think this is one of the finest reasons to read poems, that they are one of the best (and in our age only) places where we can really pay attention to the voice of another. When we read a poem, as opposed to being in conversation or watching a person on television, we have the leisure to listen to the words over and over again. The different-ness of the other person does not have to wholly disappear into the need to make contact, to grab hold of the ‘message.’ When we read a poem our first impulse is, surely, to see what it says to us that we already know, or know about. After all, the poem seeks to make contact, and we seek to make contact with the poem. But the person speaking through the poem is not me, nor you: she is another person, and just as in life, we should not be in a hurry to turn everyone into a replica of ourselves.

There is a very strange story

by Henry James called “The Beast in the Jungle.” [Want to read it

online? The Beast

in the Jungle] In it a rather self-analytic young man, John Marcher,

meets a young woman named May Bartram. She is a companion to him

through life, sharing with him his recurrent sense that something special

will someday happen to him. So self-absorbed is Marcher, though,

that he fails to recognize that what is happening to him is that he has

become oblivious to the love that is offered him by May Bartram.

He has a final opportunity to recognize this love and embrace it, but fails

to do anything. And then this discussion occurs:

He tried for a little to make out what they had; but it was as if their dreams, numberless enough, were in solution in some thick cold mist through which thought lost itself. “ It might have been that we couldn’t talk?”I know of no other passage in all of literature which makes this point as strongly. Each person speaks to us from “the other side.” Only fools and blind men cannot see that there is a point of view different from their own. And that every human being, every single one, has a unique and consequently different way of viewing the world from my way, or your way.“Well,”—she did her best for him—“not from this side. This, you see,” she said, “is the other side.”

“I think,” poor Marcher returned, “that all sides are the same to me.”

In the poem someone is speaking to us, and although the words might fit us, might speak for us, they are also in a most powerful sense the voice of another. An other. An other person. To dissolve all the strangeness of a poem so that it seems fully familiar is to wipe away the existence of the person speaking to us, to dissolve all human difference. Thus, the poem must remain strange even as we try to hear what it is saying and make sense of it.

The third dimension to poems which makes them strange to us is also something we have encountered already. Most poems are economical and compact, saying a great deal in a few words. Ezra Pound was, I believe, the greatest teacher of poetry in the twentieth century, a statement which can be supported by the fact that he personally taught a great many fine poets – Eliot, Williams, Frost, Hilda Doolittle, William Butler Yeats – how to be even better poets.

Ezra Pound

Ezra Pound

He wrote a short little book to teach people how to read poems, a primer of reading, and called it The ABC of Reading. At the very heart of his book was a discovery which Pound, a notorious amateur scholar and bibliophile, found when browsing through an antiquated German-Italian dictionary. The German term “dichten,” which means to make poetry, was translated by the Italian term “condensare,” which means what it seems it might mean, to condense. Poetry is always condensed. And in the process of reducing the number of words so that the experience or emotion is as intense in language as it is in life, things are left out or jammed together. Leaving things out is called ellipsis, and it can make for strangeness in language to those of us who are used to one thing connecting up to another. Jamming things together means that lots of explanatory material, lots of linkages, are lost. In ordinary speech, we sprinkle phrases like “I mean” and “That is to say” into our utterances, and add plenty of hesitations like “um” and “uh” so that we have time to find the words and our listeners have time to take them in; in the poem not only are these left out, but transitional material is often not provided. The mind may leap from one thing to another because they are similar, but in ordinary language we try to smooth out those jumps. Not so, often, in poems, which discard many words and phrases because of the need to condense. No wonder poems often seem strange to us: they are concentrated utterances. Not to mention that, in attempting to leap more directly from the thought or perception into language than we do in everyday conversation, poems can seem strange because their structure is not mellowed by the process of ‘making sense.’ The condensation and urgency of poetic speaking, then, will often make the poem strange to us.

There

is a fourth dimension to strangeness in the poem. The best approach

to this function of the poem is through an essay published in Russia in

1917, Victor Shklovsky’s “Art as Technique.” [You can read the whole,

stunning, essay at Art

as Technique] The critic Shklovsky quotes a passage from Leo

Tolstoy’s diaries,

Shklovsky

Tolstoy

Shklovsky

Tolstoy

where the author of War and Peace and Anna

Karenina wrote,

I was cleaning a room and, meandering about, approached the divan and couldn’t remember whether or not I had dusted it. Since these movements are habitual and unconscious, I could not remember and felt that it was impossible to remember – so that if I had dusted it and forgot – that is, had acted unconsciously, then it was the same as if I had not. If some conscious person had been watching, then the fact could be established. If, however, no one was looking, or looking on unconsciously, if the whole complex lives of many people go on unconsciously, then such lives are as if they had never been.

Shklovsky goes on to a remarkable reading

of this remarkable passage:

And so life is reckoned as nothing. Habitualization devours works, clothes, furniture, one's wife, the fear of war. "If the whole complex lives of many people go on unconsciously, then such lives are as if they had never been." And art exists that one may recover the sensation of life; it exists to make one feel things, to make the stone stony. The purpose of art is to impart the sensation of things as they are perceived and not as they are known. The technique of art is to make objects "unfamiliar", to make forms difficult, to increase the difficulty and length of perception because the process of perception is an aesthetic end in itself and must be prolonged.

I think we could all agree, to a large extent at least, with Shklovksy’s

assertion that “art exists that one may recover the sensation of life;

it exists to make one feel things, to make the stone stony.” But

what is astonishing is the move he makes from this assertion to a second

assertion: “The technique of art is to make objects ‘unfamiliar’, to make

forms difficult, to increase the difficulty and length of perception.”