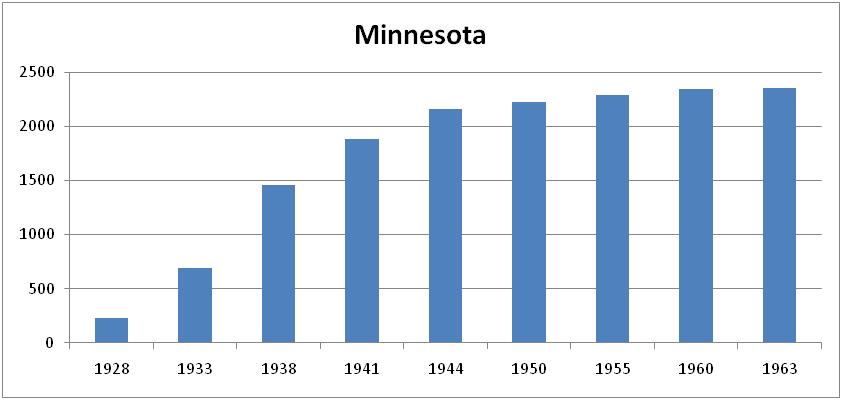

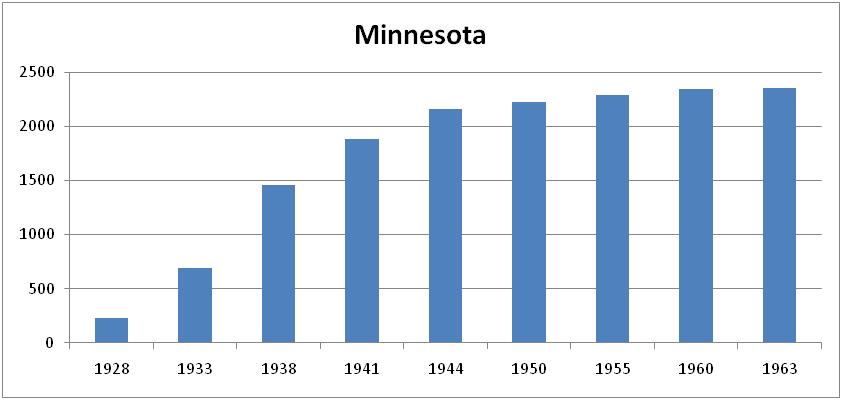

Number of victims

In total, there were 2,350 victims of sterilization in Minnesota.

Of the 2,350, 519 were male, and 1,831 (approx. 78%) were female. About

18% were deemed mentally ill and 82% mentally deficient. The

sterilizations in Minnesota accounted for 4 percent of all the

sterilizations in the nation (Lombardo, p. 118).

Period during which sterilizations occurred

The sterilizations took place predominantly between 1928 and the late

1950s. Sterilizations were relatively high in the 1930s and early

1940s (Paul, p. 393). During the war, there was a shortage of

staff, which may be the reason why there were fewer sterilizations from

1942 to 1946 (Paul, p. 396).

Temporal pattern of sterilizations and rate of sterilization

Eugenics was popular in Minnesota in the 1930s, but by the early 1940s,

social workers and officials in the state were opposed to it.

Minnesota became much more selective with its sterilizations in the

late 1940s and early 1950s (Ryan, p. 272). There were about 135

sterilizations per year between 1928 and 1944. The rate was about 5

sterilizations per 100,000 residents per year during the peak

period.

Passage of law(s)

Minnesota’s sole sterilization law was passed on April 8, 1925, making

it the seventeenth state to pass such legislature (Reierson, p. 11).

The law was formally voluntary in nature, and would stay in the

Minnesota law books almost unchanged for fifty years.

Minnesota also passed a marriage law in 1901, which "forbade the

marriage of any woman under the age of 45 or any man of any age that

was likely to father children, if either partner was epileptic,

imbecilic, feeble minded, or afflicted with insanity" (Hudulla, p. 31).

Groups identified in the law

Prior to the passage of the sterilization law in 1925, the Children’s

Code passed in 1917 "included a civil commitment law that empowered

county probate judges to commit neglected, dependent, and delinquent

children—and any person 'alleged to be Feeble Minded, Inebriate, or

Insane,' regardless of age—to state guardianship without the approval

of parent or kin. The guardianship was for life, unless the person was

specifically discharged. Once committed as feebleminded, a ward took on

the status of a permanent child: he or she was unable to vote, own

property, manage his or her financial affairs, or marry without the

state’s approval" (Ladd-Taylor, "Eugenics and Social

Welfare in New Deal Minnesota", p. 119). Given the strength of social

Progessivism, the emphasis in applying this code was on individuals who

were considered feebleminded, who could presumably be helped by social

programs ameliorating their conditions and preventing them from having

offspring that they were considered incapable of raising well.

Those groups identified in the 1925 sterilization law were the

"feeble-minded" and insane persons having been institutionalized or

hospitalized for at

least six months (Reierson, p. 11). “The law provides that

feeble-minded and insane in state institutions may be tubectomized or

vasectomized upon the advice of the state board of control, the

superintendent of the state school for feeble mindedness, a reputable

physician or psychologist, provided or his or her legal representative

gives consent” (Landman, pp. 89-90). Eugenics enthusiast Charles F

Dight estimated there to be 80,000 to 100,000 "morons and mental

defectives" in Minnesota alone, and 5,000,000 in the entire United

States (Dight, p. 28).

Process of the law

Upon

passage of the 1925 sterilization law, institutionalized

"feeble-minded" and insane could be sterilized in the state of

Minnesota. It only applied to persons under state gudaridanship. For a

ward considered feebleminded, the state board of control could give

consent, but only if no spouse of nearest kin could be located, who

otherwise would have had to provide written consent. Sterilization also

required assent by the superintendent of the state school for the

feebleminded, and by a psychologist and physician (Ladd-Taylor,

"Eugenics and Social

Welfare in New Deal Minnesota", p. 120).

The consent itself was very

carefully documented. Minnesota officials recorded consent of both the

patient and kin as well as “basic demographic information like birth

date, IQ and country of residence in a medical record book of the first

1,000 sterilization operations preformed” (Ladd-Taylor, "Eugenics and

Social

Welfare in New Deal Minnesota," p. 127). Often the consent of the

individual who was considered feebleminded was obtained, even though it

was not legally necessary.

Minnesota's law was formally voluntary. However, families were sometimes told that release from the state

institutions would proceed "more easily and satisfactory" if patients

consented to sterilization (Ladd-Taylor, "Eugenics and Social Welfare

in New Deal Minnesota", p. 128). Though it was not specifically stated

that individuals would be released if they consented to sterilization,

it was implied that they would have more success if they obliged to

sterilization.

As Ladd-Taylor ((Ladd-Taylor, "Eugenics and Social

Welfare in New Deal Minnesota", p. 119) has pointed out, "a mentally

ill person committed to the custody of the superintendent of the state

hospital for the insane could be sterilized only if he or she had been

a patient in the institution for six consecutive months. Both the

patient and the next of kin had to give their written consent. It is

not surprising, given the statutory requirements pertaining to

institutionalization and personal consent, that fewer than 20 percent

of sterilizations in Minnesota were performed on the insane."

Precipitating factors and processes

Minnesota was considered to have an outstanding program of legal

guardianship for people who had mental disabilities, and the state’s

School for the Feebleminded in Faribault was considered among the best

custodial institutions (Ladd-Taylor, “‘Sociological Advantages’ of

Sterilization,” pp. 282-83). This reflects the strength of

progressivism in the state, which also manifested itself in extensive

intrusions by courts and social workers into family life. The

reason that such intrusions were considered necessary and important for

the well-being of families was that with expansion of intelligence

tests, the number of the “feeble minded” increased, with a subsequent

increase in the number of people committed as feeble minded.

Judges committed feeble-minded people to the guardianship of the state

without consent of the parent or guardian (Ladd-Taylor, “‘Sociological

Advantages’ of Sterilization,” pp. 285-86). Judges and social workers

forced their attention on those who were considered beyond the benefit

of public assistance, particularly those who were already in trouble

with the law or welfare agencies as well as unmarried mothers

(Ladd-Taylor, “‘Sociological Advantages’ of Sterilization,” p. 287).

Yet their commitment in high numbers led to overcrowding and in the

Depression of the 1930, when the system of parole and family support

broke down (Ladd-Taylor, “‘Sociological Advantages’ of Sterilization,”

p. 293). “Frustrated by high case loads, disjointed relief

policies, and limited resources, a significant number of Minnesota

welfare workers concluded the ‘eugenic’ sterilization was a viable and

indeed humane solution to the seemingly endless cycle of family

poverty, dysfunction, and delinquency (Ladd-Taylor, “‘Sociological

Advantages’ of Sterilization,” p. 239).

One of the larger precipitating factors was the development of the 1917

Children's Code. The code, composed of thirty-five laws in it's

entirety, included a law which granted "country probate judges the

power to commit neglected, dependent or delinquent children, as well as

those deemed 'Feeble Minded, Inebriate, or Insane' to state

guardianship" (Reierson, p. 10). Along with granting the state the power

to commit a feeble minded child, the code created administrative bodies

to oversee the process of committing an individual to state custody. A

state children's bureau, child-welfare bureau were created to lengthen

the arm of the law (Ladd-Taylor, "Coping with a 'Public Menace,'" p. 239). Minnesota's mother's pensions

and juvenile court laws were revised in the process, and the state made

a commitment to providing illegitimate children with the same support

and education as children whose parents were lawfully married.

(Ladd-Taylor, "Coping with a "Public Menace,'" p. 239) The passage of this law was in many

ways the starting point of eugenics laws in that it committed children

deemed unfit to state custody, thus taking away an individuals right to

their own body. Compulsory commitment laws allowed the state to

legally obtain access to children (Reierson, p. 10).

In Minnesota, eugenic sterilizations were routine during the Inter war

period because they serve a variety of functions in the state’s welfare

system. For social workers, it made their jobs more manageable because

it reduced the numbers of the “feeble minded.” For some families,

various kinds of contraception were unavailable, so the sterilizations

were forms of birth control. For eugenicists, it was a launching point

that would lead to more stringent fertility laws for the unfit.

And for welfare officials, the sterilizations reduced public

expenditures by at least shifting them to another level of the

government (Ladd-Taylor, “‘Sociological Advantages’ of Sterilization,”

p. 295).

By the 1930s, Minnesota was considered to be the most

“feeble minded-conscious” state in the United States because of its

comprehensive program for people living with mental disabilities

(Ladd-Taylor, “‘Sociological Advantages’ of Sterilization,” p. 283).

The greatest number of sterilizations in Minnesota took place in the

1930s because relief rolls expanded due to the Depression.

In the 1930s and 1940s, sterilizations in Minnesota were rather high as

a result of people’s belief that the ward had the ability to raise a

family. (Before 1946, more feeble-minded people were sterilized in

Minnesota and Michigan than in the entire South combined.) Today

however, we do not feel the same way. In fact, from 1945 on, the

number of sterilizations results from the belief that surgery is not

always the best way to deal with the mentally retarded. People started

to care about what was best for the patients holistically, discussing

their sterilizations by respecting the patients’ will (Paul, p. 393).

There were fewer sterilizations during World War II not because of

knowledge about Nazi eugenics, but because there was a shortage of

medical and nursing persons.

Support for eugenics began to fade in the 1960s as general knowledge of

genetics grew. As the public became more accepting of individuals with

mental disabilities the field of mental health began to change, and

eugenics laws began to be challenged. (Ladd-Taylor, "Coping with a 'Public Menace,'" p. 246)

And, even though there was a scandal over the sterilizations

performed

at the state institution, sterilizations continued but were reduced in

number until 1975, when the law was changed (Ladd-Taylor,

“‘Sociological Advantages’ of Sterilization,” p. 282). However,

sterilization is still permitted upon a court order (Ladd-Taylor, "Coping with a 'Public Menace,'" p. 246).

Groups targeted and victimized

“Defective” individuals included the feeble-minded and insane persons

that were hospitalized. Most of the sterilizations were of poor,

sexually active women who violated the traditional standards of

morality and allegedly had children who they could not support

(Ladd-Taylor, “Coping With a 'Public Menace,'” p. 243). As Molly

Ladd-Taylor put it, “most women sterilized in Minnesota during the

inter war years were either young sex ‘delinquents,’ often unmarried

mothers, who were committed as feeble-minded through the court system,

or slightly older women with a number of children on public assistance”

("‘Sociological Advantages’ of Sterilization,” p. 289).

One of the known victims was Lola. She came from a family in which her

father had committed suicide and her mother, a polio survivor, was

deemed incompetent by social workers. Lola was sent to a correctional

facility at age sixteen after authorities suspected her to have had sex

with older men repeatedly. She was sterilized in 1938 at the age of 21.

She was “a girl who needs a family… [and] got sterilized instead”

(Ladd-Taylor, “‘Sociological Advantages’ of Sterilization,” p. 290).

Another known victim was an eight-teen old girl by the name of

Edna Collins. She was the ninety-eight person to become legally

sterilized from Faribault (Ladd-Taylor, "Coping with a 'Public Menace,'" p. 237). She was labeled as

feeble minded. Six weeks after her operation

Edna was healthy enough to be discharged and moved from the school to

the Harmon Club, a home for feeble minded girls located in Minneapolis.

(Ladd-Taylor, "Coping with a 'Public Menace,'" p. 237). Later the following year Edna was readmitted to

Faribault.

Ida Henderson was thirty-two years old when she was sterilized. Her IQ

score of 51 placed her into the "moron" category, which by Minnesota

law made her suitable for sterilization (Reierson, p. 1). Soon after

her mother's consent was given, Ida Henderson was sterilized. Four

months after sterilization Ida was returned to the institution because

she could not adjust life outside of the Faribault school. (Reierson,

p. 26)

An interesting known sterilization case is that of Tena and Stewart.

Tena was pregnant with her fourth child Stewart had a drinking

problem, when administered an IQ test both were found to be

"feeble minded". What is interesting about their case is that both

husband and wife were "committed to state guardianship, sent to a state

institution, and sterilized" (Ladd-Taylor, "Eugenics and Social Welfare

in New Deal Minnesota," p. 117). In this case it was the couple's

economic situation which qualified them for sterilization.

Major proponents

(Photo origin: Minnesota Historical Society; available at http://www.mnhs.org/library/tips/history_topics/117eugenics.html)

(Photo origin: Minnesota Historical Society; available at http://www.mnhs.org/library/tips/history_topics/117eugenics.html)

Charles Fremont Dight was the founder of eugenics in

Minnesota. Dight was a physician in Minneapolis, who believed

that the state should control the reproductive patterns of the

unfit. He was born in Mercer, Pennsylvania in 1856. Dight

graduated from University of Michigan in 1879 with a degree in

medicine. He eventually moved on Faribault, where he served as

resident physician at Shattuck School until 1892. This might have

been Dight’s first experience with the mentally handicapped, and their

institutions, which also happened to be the same place as the Minnesota

School for the Feeble minded (Phelps, p. 100). After taking some time to

travel and teach in Syria at the Medical College in Beirut Dight returned to in 1913 Minnesota

to teach at Hamline University (Hudulla, p. 4). In 1913 Hamline medical school fused

with the University of Minnesota. Dight continued to teach pharmacology

at the University of Minnesota until 1933 (Sonderstrom, p. 99).

Dight was an outspoken socialist who had served on the Minneapolis city

council before he took on eugenics (Ladd-Taylor, "Coping With a 'Public

Menace,'” p. 241). Eugenics was not his only focus, Dight also had many

other ideas for improving the general lifestyle of society. For

instance he argued that Minneapolis should feed its garbage piles to

pigs instead of burning it (Carlson, p. 132). Much like his views,

Dight's personality was also quite eccentric, he built and lived in a

tree house in Minneapolis for many years (Carlson, p. 133).

It was no until the early 1920s that Dight began his

attempts to create a eugenics movement in Minnesota (Hudulla,

p. 4). The question Dight was asking of society was "why is there

crime and degeneracy?" (Carlson, p. 133) Dight believed the answer to

this lay in individual genes. He believed that individuals who were

"defective" were so because of innate characteristics that could not be

altered. He pushed for eugenics education, changes in

the marriage laws, and the segregation and sterilization of these

“defective”

people. In Dight's eyes, the only way to prevent crime was to prevent

criminals and degenerates from reproducing (Carlson, p. 135). In fact,

Dight sought to create a Utopian society, free from "degenerates"

(Carlson, p. 142). Dight believed that "eugenics would not simply make

a better world, it would create a perfect world (Carlson, p. 142). He

argued for sterilization by saying that a house "cannot be made out of

rotting lumber" (Carlson, p. 132). Dight organized the Minnesota

Eugenics Society in 1923

and started to campaign for a sterilization law. He launched a

legislature crusade for the sterilization of the “defectives.” He

did not think that that segregation of the unfit was enough; they

needed to be sterilized so that they did not pass their undesirable

traits through procreation (Phelps, p. 101). Dight often used a

metaphor of "keeping an ambulance at the foot of a cliff to carry to

the hospital the people who fall over" (Dight, p. 28). Instead he

argued, a railing should be installed in order to prevent people from

falling off the cliff in the first place. The railing, in this case

represented a suitable sterilization law (Dight, p. 28).

Dight argued that mental inferiority could be easily identified by two

things: jazz and skull shape. Jazz, according to Dight was the 'devil's

kind", and was enjoyed more by the inferior because it appealed to

their "inborn animal nature" (Hudulla, p. 9). Craniometry the study of

the size and shape of skulls/brains was also a crude tool used by Dight

to assess mental capabilities. His argument is that "great men" have

larger fore heads representing their larger frontal lobe, where

as "lower animals" including the feeble minded and inferior would have

smaller foreheads (Hudulla, p. 9). Dight's beliefs on craniometry

ultimately stemmed from a professor of clinical surgery: Paul Broca. As

a "cure" for mental defectives Dight turned to the well known practice

of farming. He argued that much like a farmer would bred his two

healthiest animals together, humans should also only breed the best

with the best. Dight sought to extend breeding practices to humans

(Hudulla, p. 25). Not only should humans stop the unfit from

reproducing, but he breeding of "thoroughbred should be encouraged.

(Hudulla, p. 26). To properly execute human breeding Dight suggested to

"learn if feeble-minded-ness, insanity, epilepsy, or repeated

criminality have existed during the last three generations" of your

potential mate (Hudulla, p. 30). In this way Dight hoped to prevent the

marriage of the reproductively unfit (Hudulla, p. 30).

Dight’s biggest adversary was the Catholic Church,

who opposed his ideas on moral grounds (Phelps, p. 104).

Interestingly enough Dight often used religion as a reason and as

support for eugenics. He argued that Jesus condemned the "unfit", using

a familiar bible quote "and every tree that bringeth not forth good

fruit is hewn down and cast into the fire" as a pro sterilization

argument (Carlson, p. 139). The American Eugenics society even

published "A Eugenics Catechism" in

which they combated potential arguments from the religious community.

(Hudulla, p. 14). Despite the printing of "A Eugenics Catechism" and

Dight's frequent use of biblical metaphors in defense of eugenics, few

in the religious community were swayed. It is not surprising then that

Dight also expressed distaste of the church, as well as the state and

educational system. His argument was that you cannot change individuals

from the inside out and that the church, state and educational systems

were wasting time and resources trying to alter the inevitable

(Carlson, p. 135). In fact Dight specifically attacked the church on

many occasions calling it the "uplifter reformer" and mocking it for

its "coddling and forgiving treatment" (Carlson, p. 136). Dight instead

believed that "training after birth cannot undo a bad inheritance"

(Carlson, p. 136). Education and religion were only temporary fixed,

and in the long run did not achieve results (Carlson, p. 137).

Foremost

among Dight’s goal was convincing the state legislature to enact

encompassing sterilization laws for the mentally handicapped. He

confronted the legislature each biennium in this regard from 1925 to

1935” (Phelps, p. 99). Dight tried to get the sterilization law

to extend to the feeble-minded and insane persons that we not

institutionalized, but he was unsuccessful. Though he was not at

fault for his effort, often promoting his ideas to senators up to a

point of annoyance (Carlson, p. 141). Overall, he pushed

for stricter sterilization laws in Minnesota, but they did not pass.

Dight praised other eugenics movements across the world, often citing

Germany as the "shining example" of an effective eugenics program.

(Hudulla, p. 16). He would often attribute Germany's success as support

for the American eugenics movements. According to Dight, Germany's

orderly society was a direct result of their efficient eugenics

programs (Hudulla, p. 18). In

1933, Dight wrote a letter to Adolf Hitler wishing Nazi efforts in

eugenic sterilization “to be a great success” and noted in a letter to

the Minneapolis Journal that “if carried out effectively, [compulsory

sterilization of the disabled] will make [Hitler] the leader of the

greatest rational movement for human betterment the world has ever

seen” (http://www.chgs.umn.edu/Histories/letterHitler.pdf). Dight hoped

to inspire future eugenics movements after his death. Though he died in

1938, he devoted much of his life savings to fund the creation of the

Dight Institute for Eugenics on the University of Minnesota Campus

(Carlson, p. 132). The name has since been changed to the Dight

institute for the Promotion of Human genetics (Carlson, p. 132).

Fred Kuhlmann was a psychologist and an important

proponent of eugenics. He served as the Director of Research at the

Faribault school from 1910 to 1921 (Reierson, p. 18). After leaving

Faribault Dr. Kuhlmann took up the post of the head of the Research

Bureau of the State Board of Control (Reierson, p. 18). During his time

at Faribault Dr. Kuhlmann was responsible for the administration and

the interpretation of psychological testing. He revised the Binet-Simon

Test in 1920, dubbing it the Kuhlman-Binet test, and administered it in

order to identify “high grade” mental defectives (Reierson, p. 17). Dr.

Kuhlmann was responsible for the increase in the number of Minnesotans

who were labeled feeble minded (Ladd-Taylor, “Coping With a 'Public

Menace,'” p. 240). His paper entitled "The Larger Aspects of the

Special Class", Kuhlmann asserts that "subnormal children" were half of

all social trouble (Reierson, p. 19).

Mildred Thomson was in charge of the control board’s

bureau for feeble minded and epileptic from 1924 to 1959. Her position

at

the head of the control board bureau made her, by law, the guardian of

the wards of state hospitals (Ladd-Taylor, "Eugenics and Social Welfare

in New Deal Minnesota," p. 124). Though Thomson

considered herself primarily a social worker, she studied at Stanford

University where she wrote her thesis on the IQ testing of school

children (Ladd-Taylor, "Eugenics and Social Welfare in New Deal

Minnesota," p. 124). She worked closely with both Dight and

Kuhlmann.

Execution of the Law

Sterilizations began at the School for the Feeble minded on January 8,

1926. George G. Eithel preformed the first 150 surgeries, after

his death in 1928 his nephew George D. Eithel would take over.

(Reierson, p. 22). The Faribault School for the Feeble-minded was the

only location in Minnesota where sterilization of the mentally

handicapped were preformed (Hudulla, p. 31). Once individuals had been

lawfully committed to an

institution they would often work at their respective institutions as

low-wage workers. (Reierson, p. 13). High-grade inmates were expected to

work in order to "pay" for room and board. Sterilizations were often

preformed on site, it was common for Dr. Eithel to travel to Faribault

to preform free sterilizations (Reierson, p. 17). Once individuals had

been sterilized they were either released, or sent to "clubhouses".

Approximately a fifth of the inmates released from institutions were

sent to clubhouses. (Reierson, p. 13). The clubhouse was set in place as an

intermediate step between institutionalization and the "real world".

Clubhouses allowed individuals to have a greater sense of independent

living, while still under constant supervision. In this way, the

procedure of segregation was again assimilated into eugenics programs.

Clubhouses opperated under the reward system, granting inmates more

freedom depending on their levels of mental deficiency (Reierson,

p. 13). During the Great Depression the clubhouse system would collapse

due to a lack of funding.

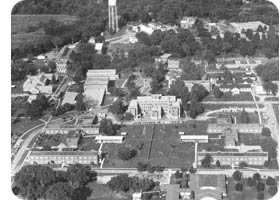

“Feeder institutions” and institutions where sterilization were performed

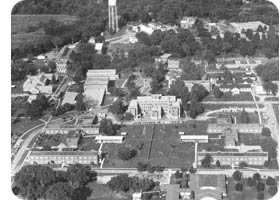

Photo

origin: Minnesota Governor's Council on Developmental

Disabilities; available at

http://www.mnddc.org/past/1990s/1990s-3.html)

Photo

origin: Minnesota Governor's Council on Developmental

Disabilities; available at

http://www.mnddc.org/past/1990s/1990s-3.html)

The Faribault State Hospital in Minnesota served the

entire state until the late 1950s. The school was first opened in 1879

under the name of the School for Idiots and Imbeciles, two years after

the school began collaborating with the Minnesota Institute for the

Deaf Dumb and the Blind. (Reierson, p. 15) The combination of the

two institutions was then named the Minnesota Institute for Defectives.

In 1901 the name was again changed to the School for the Feeble-Minded

and Colony of Epileptics (Reierson, p. 15). Patients in the institution

were of all ages and had varying degrees of mental retardation. The

school was created with three main objectives in mind: to function as a

trade-school type education, as shelter for those who could not take

care of themselves and to care for children whose parents were unable

to (Reierson, p. 16). In the 1940s however another principle was added,

the school would also act as a home for those who are a menace to

society (Reierson, p. 16).

Dr. Arthur C. Rogers led the School for

Feeble minded, as superintendent, from 1886 to 1917. In 1910 Dr. Fred

Kuhlmann, a research psychologist from Clark University, was invited to

assist Dr. Rogers as the Director of Research (Reierson, p. 16). As

director, Kuhlmann was asked by Dr. Rogers to try and establish more

tangible evidence of mental deficiently caused by heredity (Reierson

p. 16). With the assistance Charles Davenport and ERO fieldworkers

Rogers and Kuhlmann were able to create a pedigree of all the school’s

inmates and compile the results into a book he named Dwellers in the

Vale of Sidden (Ladd-Taylor, “Coping With a ‘Public Menace,’” p. 239).

Dr. Rogers died in 1917 and was succeeded by G.C. Hanna. Sterilizations

began with the passage of the law in 1925. A surgeon by the name of

George G. Eithel would frequently make a fifty-mile journey to

Faribault to perform sterilizations on inmates free of charge

(Reierson, p. 17). Dr. James Murdoch would take over the position of

superintendent when Hanna died. During Murdoch’s time as superintendent

the school went through its greatest grown period, between 1920 and

1932 the population increased by 500 residents to a grand total of

2,217 (Reierson, p. 17). Often the doctors of the school would

offer summer courses with the goal to educated like-minded people and

expand the number of institutions. It was one of the nation’s foremost

institutions for the feeble minded. The school was re-named to the

Faribault Regional Center, and then again to the Faribault State School

and Hospital before it closed. The institution closed on July 1, 1998

and was replaced by a correctional facility (Ladd-Taylor, “Coping With

a 'Public Menace,'” p. 246).

The Harmon Club was established in 1942, as a place for women to go

during "parole" (Ladd-Taylor, "Coping with a 'Public Menace,'" p. 244) Once women were discharged they

would be moved to the Harmon Club in Minneapolis. The club was

considered to be an intermediate between the Faribault School and the

community where women could live more independently and inexpensively

(Ladd-Taylor, "Coping with a 'Public Menace,'" p. 244). Unfortunately the Harmon Club as well as the two

other club houses in St. Paul and Duluth felt the effects of the Great

Depression and closed in the 1930s (Ladd-Taylor, "Coping with a 'Public Menace,'" p. 244)

Opposition

American Catholics were the main opponents of Eugenics (Leon), and

social workers and some state officials opposed it as well (Ryan, p.

272). Though not all of the press coverage given to the eugenics

movement was negative, the media was generally critical, labeling

eugenics as a "war of the wealthy against the poor" (Reierson,

p. 9) Overall, however, there was very little public discussion

about the feeble-minded, which resulted in indifference towards them.

However there were a few who challenged the sterilization practices. Of

the total one thousand recorded sterilizations, seven men and seventeen

women attempted to flee the institution (Reierson, p. 23).

Unfortunately, the inmates rarely succeeded in avoiding sterilization.

The reason being that any resistance on the part of the inmate, or

general public was

attributed to their low IQ, and not to the practice of sterilization.

Due to the lack of organized opposition, one individual's criticism

against an "organized and mobile eugenics machine" (Reierson, p. 10) was

often ignored.

One case stood out beyond all others, Rose Masters was a

"Catholic farm wife and mother of ten" (Ladd-Taylor, "Eugenics and

Social Welfare in New Deal Minnesota", p. 132). Though their children

were normal, agents from the country welfare board repeatedly showed up

at the farm. Mrs. Masters was sent to the state institution in 1942,

three months following her neighbors petitioned her release. The case

went up all the way to the Minnesota Supreme court and she was

eventually released. (Ladd-Taylor, "Eugenics and Social Welfare in New

Deal Minnesota", p. 132). In another important case in 1944 the

Supreme Court ruled that the burden of proof was not on the individual

but the state welfare board. (Reierson, p. 14).

Bibliography

Carlson, Jessie A. 2009. "Eugenic Sterilization: The Final Solution for America". Undergraduate Research Journal at UCCS 2, 1. Available at <http://ojs.uccs.edu/index.php/urj/article/view/56/64> .

Dight, Charles F. 1935. "History of the early stages of the organized

eugenics movement for human betterment in Minnesota." Minneapolis: Minnesota Eugenics

Society.

Hudalla, Justin W. 2001. "The Human Garden Needs Weeding: Charles F.

Dight and Eugenics in Minnesota, 1920-1938." Undergraduate Thesis, Dept. of History, University of Minnesota at Minneapolis.

Ladd-Taylor, Molly. 2011. "Eugenics and Social Welfare in New Deal

Minnesota." Pp.117-140 in A Century of Eugenics in America, ed. P. Lombardo.

Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

--------. 2005. "Coping With a 'Public Menace': Eugenic Sterilization in Minnesota." Minnesota History 59, 6: 237-248.

-------. 2004. “The ‘Sociological Advantages’ of

Sterilization: Fiscal Politics and Feeble minded Women in Inter war

Minnesota.” Pp. 281-99 in Mental Retardation in America: A Historical

Anthology, eds. S. Noll and J. Trent. New York: New York University

Press.

Landman, J. H. 1932. Human Sterilization: The History of the Sexual Sterilization Movement. New York: MacMillan.

Leon, Sharon. 2004. "Hopelessly Entangled in Nordic Pre-suppositions:

Catholic Participation in the American Eugenics Society in the 1920s."

Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 59, 1: 3-49.

Paul, Julius. 1965. "'Three Generations of Imbeciles Are Enough': State

Eugenic Sterilization Laws in American Thought and Practice."

Washington, D.C.: Walter Reed Army Institute of Research.

Phelps, Gary. 1984. "The Eugenics Crusade of Charles Fremont Dight." Minnesota History 49, 3: 99-109

Reierson, Sondra. 2006. "Eugenics in action: Minnesota and the

Faribault School for Feeble minded." Undergraduate paper, College of Saint Catherine.

Ryan, Patrick J. 2007. "'Six Blacks from Home': Childhood, Motherhood,

and Eugenics in America." Journal of Policy History 19, 3:

253-281.

Soderstrom, Mark. 2004. "Weeds in Linnaeus’s Garden: Science and

Segregation and the Rhetoric of Racism at the University of Minnesota

and the Big Ten". Ph.D. dissertation, Dept. of History, University of

Minnesota.

(Photo origin: Minnesota Historical Society; available at http://www.mnhs.org/library/tips/history_topics/117eugenics.html)

(Photo origin: Minnesota Historical Society; available at http://www.mnhs.org/library/tips/history_topics/117eugenics.html) Photo

origin: Minnesota Governor's Council on Developmental

Disabilities; available at

http://www.mnddc.org/past/1990s/1990s-3.html)

Photo

origin: Minnesota Governor's Council on Developmental

Disabilities; available at

http://www.mnddc.org/past/1990s/1990s-3.html)