Home History

Maps

Photos Historic Census Data

Resources Main Project Page |

An Agricultural History of Franklin, VT

By Jennifer Parsons, UVM

Historic Preservation Graduate Student

October, 2009

Franklin, Vermont, has thrived as an agricultural

town since 1789, despite the fact that, “the township is injured very much by a

large pond, which lies near the center.”[1] This “pond,” known during the 1800s as

Franklin Pond or Silver Lake, now known as Lake Carmi, did not prove to be the

injurious threat to the town that Zadock Thompson’s 1824 Gazetteer imagined. The 1845 poster for the Franklin County Agricultural

Fair (now known as the Franklin County Field Days) indicates the prosperity

which was achieved by farmers throughout the county: “It is hoped that the farmers of the richest

and most exclusively agricultural county in the state will feel a deep interest

in the Fair of Franklin County.[2]” Franklin clearly held a strong part in this

heritage, as residents of the town 19,400 acre town were described in 1872 as “mostly

farmers, and in general pretty intelligent and successful.”[3]

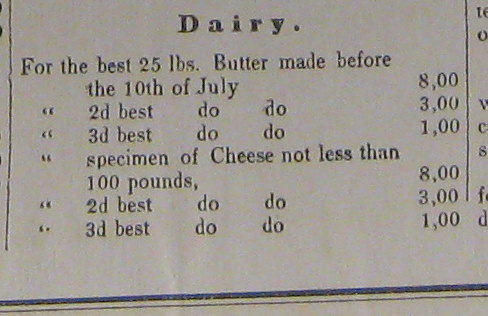

Prizes for dairy in the Franklin County Agricultural Fair.

Source: Franklin County Agricultural Society: Record Book 1844-1889. Manuscript.

University of Vermont Special Collections. |

Within the county of Franklin, the first U.S. Agricultural

Census of 1840 indicates that the town of Franklin was solidly productive in

“Value of Products of the Dairy,” with 10,680 dollars reportedly produced,

behind only Fairfield and Sheldon, and diversified in their farming interests

to also have over three times the number of sheep (6,288) as they had “neat

cattle” (1,752). Poultry, wheat, oats, rye, buckwheat, Indian corn, and wool

products were also reported, indicating a more diversified farm system than the

largely single purpose dairy farms of Franklin today, steeped solely in dairy

milk production.[4]

Governor Chittenden granted the area now known as

Franklin to Joseph Hunt in 1789, who named the area Huntsburg. Samuel Hubbard, of Northfield, MA, (and

Joseph Hunt’s nephew) achieved the first settlement in the fall of 1789, when

he brought 3 hired men, 1 yoke of oxen, and 1 cow with him and selected his ten

acre parcel. He sowed ten acres of

wheat, went back to Massachusetts, and returned the following spring. He built the first log house, frame-barn,

grist-mill and saw mill.[5] Other settlement followed, and the town had a

population of 46 by 1791.[6] Joseph Hunt never resided in Huntsburg, and

the town voted to change its name to Franklin in 1817. Surveys of the land of Franklin occurred

after the two nearby towns, Sheldon and Highgate, had already been done. This left Franklin’s 19,400 acres “a little

deficient in measure and outline.”[7]

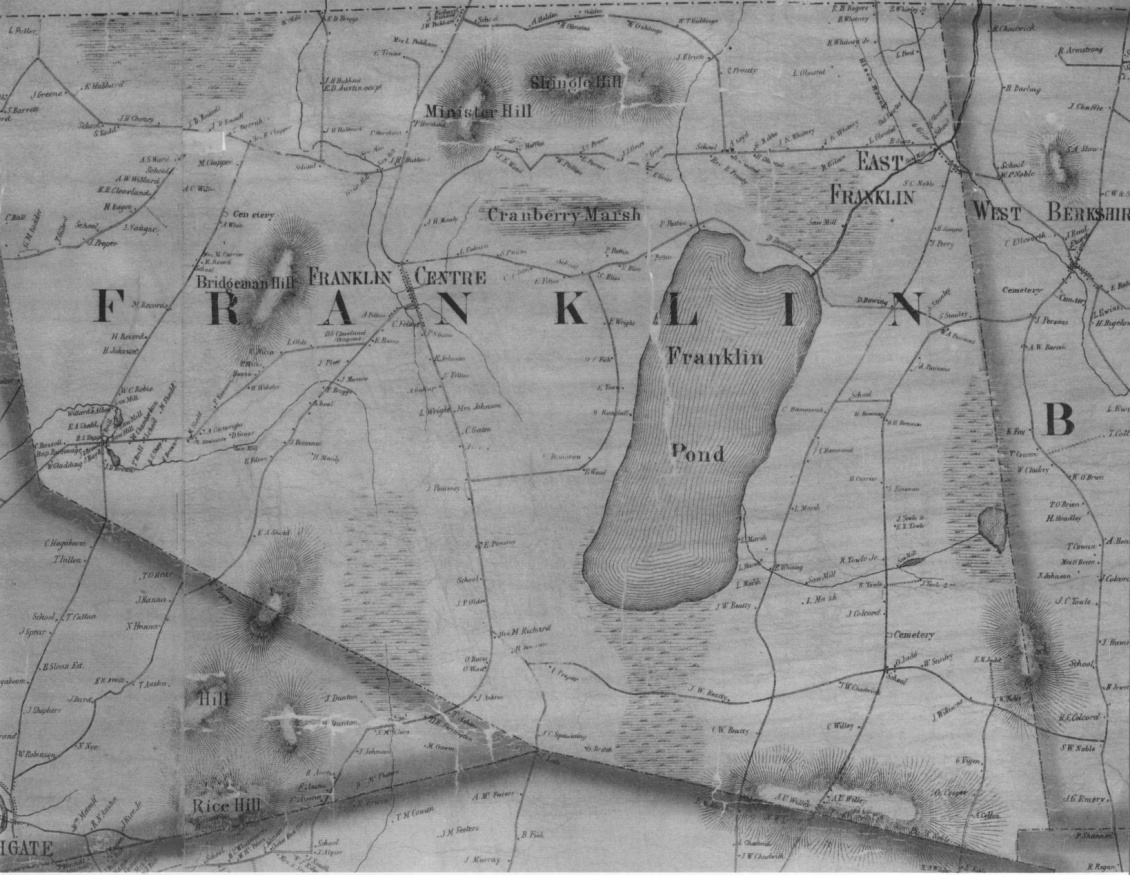

| 1857 Map of Franklin by H.F. Walling. Courtesy of UVM Special Collections. |

The soil and lay of the land proved variegated at first. With only “two hills worthy of mention,”[8]

Bridgeman Hill to the west and Minister Hill to the north, and the soil

comprised of loam, clay and sand, it provided a good mixture for agricultural

uses. Swamps containing cedar and ash

provided abundant fencing material for livestock.[9]

The soils, though slightly acidic,

offered good grassland, hay, and even, in the northeast corner of town by 1935,

“the soil is considered some of the best in the state for potatoes.”[10]

Yet, in 1789 when new settlers Uri Hill and Stephen

Royce arrived to scope their “pitch,” they expressed their disappointment in

the landscape. By the time they reached Cranberry Marsh, Royce climbed a tree

to scout the landscape and declared: “I wish the man that ever visited

Huntsburg had his tongue cut out before he had the opportunity to tell the

others what he saw.”[11] Yet, they pressed on over Minister’s Hill and

found what others found who settled there: “finally, they emerged on a hard

wood tract of land, the most beautiful they ever saw.”[12] By 1800, the population reached 280, and by

1820, it reached 631.[13]

The War of 1812 between the U.S. and the British

proved an interesting point in Franklin’s agriculture, as farmers crossed the

border into British ruled Canada frequently and with necessity. First settler Samuel Hubbard (and likely

other farmers, as well) needed to get into Canada: “His market was Montreal, as

soon as he had much to sell, that was not needed for the incoming population”[14] At the onset of the War of 1812, trade across

the US-Canada border ceased, and soldiers guarded the border, enforcing the

trade restrictions put in place by the Crown.

Troy and Albany were the other closest nearby markets, but still too far

to reach by a team of oxen, and farm produce was not valuable enough to

transport that far. These embargoes left

farmers in Franklin without a marketplace.

“But some British subjects, neighbors and friends of those who lived in

Vermont, sometimes appeared on the south side of the line, and left with their

old friends sums of money, and soon after cattle, hogs, or horses were missing

from their stalls and pens.” [15]

During

this period, a “Smugglers Road” developed from “some point on the Missisquois

River, in Sheldon, through this town on the east side of the pond, to the lines

adjoining St. Armand, and the whole distance was then an entire wilderness.”[16] Stories of outwitting the border guard and a

few local scoundrels emerge from this situation.

| Although

this photo was taken later than the War of 1812, this muddy road

indicates the kind of difficult travel a team of oxen might face in

taking a farmer's wares a great distance,before trains offered the

ability for milk products from Franklin to easily reach Boston,

Connecticut, and Montreal. | | 1917? Photographer Unknown. Franklin, VT. Source: UVM Landscape Change Program. |

Also of note from 1812 is the first entry into the Vital

Records of the town of Franklin’s section on identification marks for each

farmer’s animals. Samuel Hubbard marked

for cattle, hog, and sheep by squaring off the left ear, and cutting a

“half-peny mark on the underside of the right ear.”[17] As one of the few entries

in this book, perhaps his were animals that were smuggled, without sums of

money left by friends in St. Armand.

But the real driving force in Franklin, VT was butter

and cheese. By the Census of 1850,

92,800 lbs of butter had been produced on farms that year, and 95,030 lbs of

cheese. Fluid milk was not recorded or

sold yet. The family produced fluid milk

for its own needs, and sold the rest in a more shelf stable form—heavily salted

butter or aged cheese. An ordinary cow

gave about five or six quarts of milk a day during the prime milking season of

summer, and the rest became cheese or butter.[18] Herds of between 5 and 25 “milch cows” were

kept. By mid-century, Vermont became a

major competitor in the nation’s cheese production, ousting Connecticut and

Rhode Island in importance. The Vermont

and Canada railway, which continued the Vermont Central Rail Road to northern

points, carried over a thousand tons of cheese in 1860.[19]

With stops in surrounding communities of

Swanton, Sheldon, and East Berkshire, it’s likely that much of this cheese was

produced in Franklin.[20]

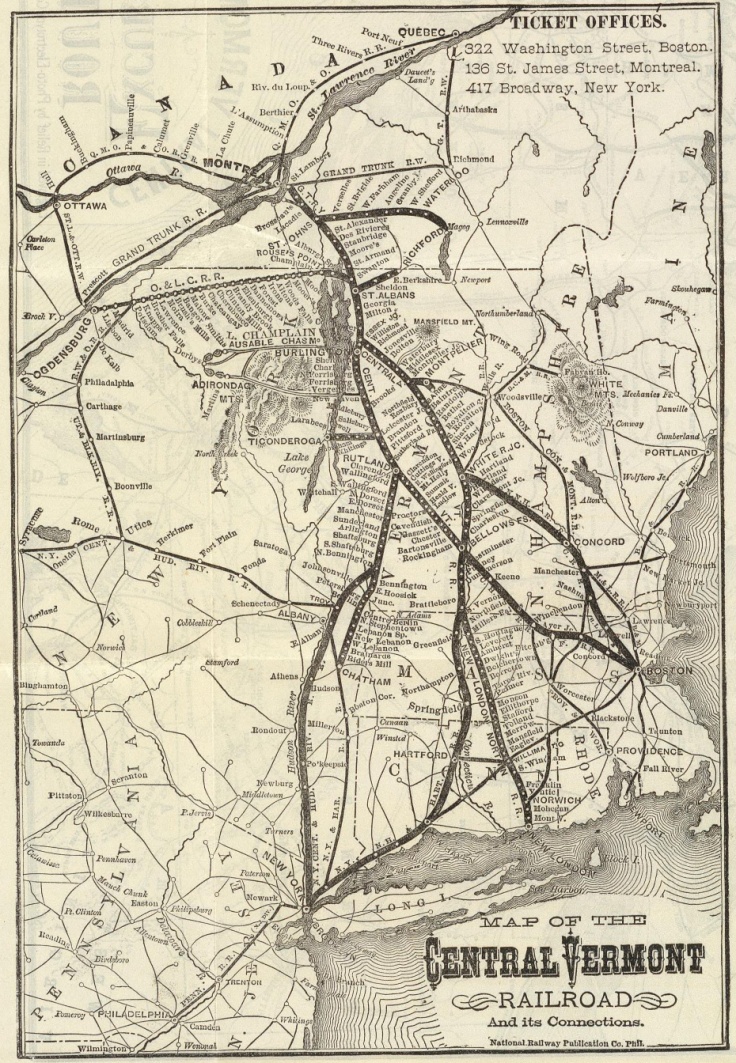

| This map of Central VT Rail Road shows connectivity with Montreal, and southern New England. | | Below: A close-up of the map, showing stops near Franklin: Sheldon, East Berkshire and Swanton. | | -Source: Central VT Railroad, 1879, Wikipedia.com |

Yet Franklin, like many towns in New England, shifted

their production towards producing more butter than cheese around the

1860s. “By 1854, iced butter cars began

to run to Boston by rail from as far as Franklin County in the northwest corner

of Vermont.”[21] Iced rail road cars allowed for butter to be

produced with less salt, thereby improving the flavor. By the time of the 1880

Census, butter churning was the primary milk product, with 314,200 lbs sold,

compared to 300 lbs of cheese.[22] As cities expanded in population, the demand

for fresh milk grew. Whereas there was

no fluid milk reportedly sold in 1840 or 1850, by 1870 around 15,000 gallons of

fluid milk were sold: a paltry number in comparison to cheese, but an

indication of things to come.[23]

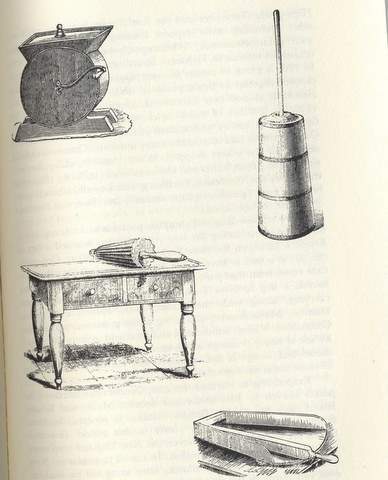

| Right: As

cheese production shifted toward butter making, women would use devices such as

these to produce their farm’s wares.

This illustration, originally from Mapes Illustrated Catalogue of 1881,

and reprinted in Howard Russell’s book A

Long, Deep, Furrow, bears the following description: “Help for the farm wife’s butter making: a)

cylindrical churn; b) dash churn; c) cylindrical butter worker; d) lever butter

worker.” |

|  | | | Left: E. Davis of Vermont proposed

this plan for a cheese press. Dairy women pressed cheese in a device

such as this illustration. "In pressing cheese, it is desirable that

the pressure should be light at first, and increase gradually toward

the end of the process. The parts (for the cheese press) are not objectionably complicated, and the price, $10, not beyond the means of dairy men generally." |

| Source: Russell, Howard S. A Long, Deep Furrow: Three Centuries of

Farming in New England. (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1976),

423. | | Source: American Agriculturist, June 1, 1860: 169. | | |

|

The number of dairy farms stayed roughly the same

through the mid-1800s, while the number of dairy cows increased toward the

1880s. In 1850, the US Census reported

131 farms and 1300 “milch” cows, and by 1880, the number of farms rose to 150, with

2,100 “milch cows.”[24]

By 1850, Franklin farms still had 3,254 sheep, almost

half of its sheep stock of ten years earlier. This remains consistent with

other Vermont agricultural trends.

Whereas Addison County led the state, and the country, in sheep

production in 1840 with eleven sheep per person, buyers from the west bought

many of the rams and ewes from Vermont’s good stock and took them west. This resulted in competition, and a loss of

Vermont’s stronghold on sheep.[25] By 1880, there were as few as 555 sheep in

Franklin, and by 1935, only 226.[26] However, contrary to the fact that sheep were

once a very active part of Franklin’s agriculture, few specific sheep barns

were located in my 2009 survey.

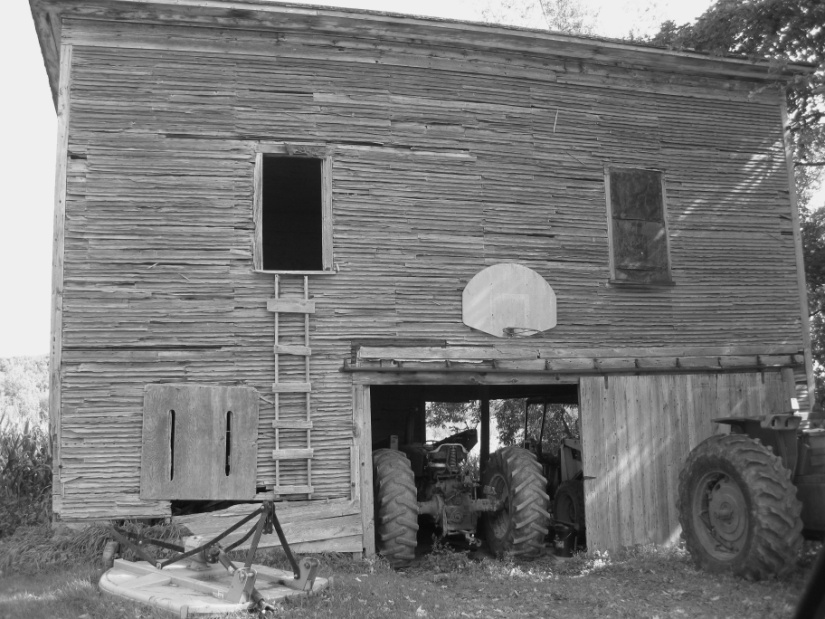

This

barn, found on Pigeon Hill Rd., may have been used for raising sheep.

Note the large door, which opens on the ground floor.

This would

allow a sheep herd to gain shelter from the rain easily, and the

hayloft above is a traditional feature of a sheep barn.

The shed roof of this structure drains to the rear side. | | 2009, Looking east on Pigeon Hill Rd., photo by Jennifer Parsons. |

The demand for fluid milk grew with growing

urbanization by the late 1800s, and railroads were the key to offering milk

from rural places such as Franklin to urban areas, at much lower prices than

their more urbanized counterparts.[27] Farmers could do quite well,

economically. Many barns were built

during this period and evidence can be found to this end by the number of

high-drive and covered high drive bank barns found throughout Franklin,

typically built toward the late nineteenth, early twentieth century and heavily

influence by new scientific approaches to farming.[28] Thus, by 1935 in Franklin, nearly all of the

milk in production from nearly the same amount of farms as there were in the

1880s, was sold in fluid form.[29] By 1945, 3100 cows on 109 farms reported for

Franklin indicates farmers had built up larger herds per dairy farm, with

average herd sizes closer to 40 than 20, as was the case a hundred years prior.[30]

Evidence of these peak years of dairy culture can be

found by examining the barn structures of Franklin that remain today. Roughly 140 historic agricultural structures were

counted in a windshield survey in October of 2009. A predominant number of these remaining

structures are bank barns, which rose in prominence in the middle of the

eighteenth century, and several examples of a latter version, the high-drive and

covered high drive bank barn.[31]

| This

well preserved example of a covered high drive bank barn, ca. 1890,

features an eaves side entrance. Here, a team of horses with wagons

could drive directly into the haymow, up above. The cows are kept in

the middle level, with a manure pit below. Though this barn does not

have two entrances, often high drive barns may have more than one

entrance, so that the hay wagon didn't need to turn around. Note the

attached grain silo build of wood to the left. | | 2009, Eaves side-entry bank barn on Richard Rd., looking east. Photo by Jennifer Parsons. |

An 1890 meeting of the Board of Agriculture in

Franklin indicates farmer’s concerns at that time. A Question and Answer session held revealed

that some Franklin farmers still raised merino sheep, and were concerned about “overproduction”

of merinos that kept prices low at that time.

Southdown sheep, raised for mutton, could be raised in larger flocks

than merinos, and farmers were advised that they could keep up to a hundred of

them—which could also provide eight pounds of wool per head. Also, eight to ten sheep could be raised in

the amount of pasture that would support one cow. Clearly, sheep production still occurred in

Franklin by 1890, although probably with considerably less vigor than before

the Civil War.

Dairy farmers also had many questions for the Board

of Agriculture. One farmer wanted to

know what effect a “Butter Extractor” would have on the industry. “The demand for butter fresh from the churn,

or in other words, butter made from sweet cream is growing and coming into more

and more favor. If this continues, the

butter from the extractor will be in demand and command the highest price. Of course, this kind of butter will not keep

long.”[32] With the Butter Extractor, aka Extractor

Separator, “the time required for churning any particular drop of milk is not

over a second.”[33] The Board also predicted the move towards

creameries producing their butter, providing uniform quality and a good price. The meeting closed with a description of the

best way to make butter in shallow pans, also know as dry open setting. Three quarters of the butter in Franklin County

was made this way, in which 4 lbs of milk could produce one pound of butter.[34]

The Board of Agriculture of 1890 predicted that dairy

farming would progress towards selling to creameries directly, although the St.

Albans Co-op Creamery was not formed until 1919. Currently, Franklin County still has more dairy cows than any other county.[35]

Franklin also engaged in maple sugar-making, and it

reported 36,925 lbs of maple sugar in 1850, with a steady increase to three

times as much by the 1880 agricultural census, and many sugar houses currently

stand.[36]

Other agricultural structures and census evidence

indicate that poultry production operated within a limited scope in Franklin,

although no census numbers were reported until t  he 1880 census, when each farm

had around 10-20 chickens, largely for home egg production. he 1880 census, when each farm

had around 10-20 chickens, largely for home egg production.

One agricultural curiosity appears in the area

labeled on Walling’s 1857 map: an area referred to as “Cranberry Marsh” and

again referred to in Hemenway’s story of first settlers in Franklin.[37] Though wild cranberries were eaten by the

Native Americans, were cranberries ever in commercial production? No census evidence was revealed, however, a

few curious structures were located nearby in my 2009 windshield survey. One structure could potentially be a

cranberry bog house, which would have held a gas or electric pump, to control

water levels.[38] On higher ground, a long, narrow, single

story structure with a side-entry may potentially have been a screen house,

where cranberries were cleaned. These

structures are located adjacent to the north of the Cranberry Marsh, or Franklin

Bog, on Middle Road. However, owing to

the limited size of the marsh, commercial cranberry culture may have been

unlikely, and conversations with locals have revealed no knowledge of any cranberry culture.

| Potential

screen house (left) and bog house (right) northwest of the Prouty

Cemetery on Middle Rd. It seems more likely that these are structures

related to dairy farming: simply a shed and a well pump. No evidence of commercial

cranberry culture was found other than this area's label on Walling's 1857 map,

"Cranberry Marsh." | | 2009, Middle Road looking north. Photos by Jennifer Parsons |

Bibliography of

Resources

Agricultural Extension Service, University of Vermont. Agricultural

Trends in Franklin, Vermont: As a report on Project Number 665-12-3-56,

Conducted Under the Auspices of the Works Project Administration. Burlington, VT: Agricultural Extension Service, University of Vermont, and State

Agricultural College, 1941.

Child, Hamilton.

Gazetteer and Business Directory

of Franklin and Grand Isle Counties, VT: 1882-1883. Syracuse, NY: Hamilton Childs, 1883.

Franklin County Agricultural

Society: Record Book 1844-1889. Manuscript: University of Vermont Special Collections.

Hemenway, Abby, ed. The Vermont Historical Gazetteer: a Magazine, Embracing a History of Each Town,

Civil, Ecclesiastical, Biographical and Military, Volume 2. Burlington, VT: Miss A. M. Hemenway, 1871.

Jeffrey, William H. Successful Vermonters: a Modern Gazetteer of

Lamoille, Franklin, and Grand Isle Counties. East Burke, VT: The Historical Publishing Company, 1907.

Jenkins, E.H. ed. USDA Bulletin: A Compilation of Analysis of

American Feeding Stuffs. Washington:

Government Printing Office, 1892.

Russell, Howard S. A Long, Deep Furrow: Three Centuries of

Farming in New England. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1976.

Thompson, Zadock. Gazetteer of the State of Vermont. Montpelier: E.P. Walton, 1824.

Town of Franklin. Vital Records and Cattle Marks. Franklin, VT: On File With Town Clerk.

1791-1854.

US Bureau of Census. Productions of Agricultural in the Town of

Franklin, Franklin County, Vermont. 1840, 1850,1860,1870,1880.

UVM and State Agricultural College, ed. Farm Census for the State of Vermont Based on the Bureau of Census

Unpublished Data, January 1, 1945.

Burlington, VT: UVM and State Agricultural College Cooperative Extension Service,

1946.

Visser, Thomas. Field

Guide to New England Barns and Farm Buildings.

Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England, 1997.

Maps:

Beers, F.W. Atlas of

Franklin and Grand Isle Counties, Vermont.

New York: F.W. Beers, 1871.

Walling, H.F. Map of the

Counties of Grand Isle and Franklin, Vermont.

New York: Baker & Tilden Co., 1857.

United States Geological Survey. Enosburg Falls, VT Topographic Map. USGS, 1924.

United States Geological

Survey. Enosburg Falls, VT Topographic

Map. USGS, 1953.

Newspaper and

Magazine:

“A New Cheese Press.”

American Agriculturist, June 1, 1860: 169.

“Farmers at Franklin: Close of the Board of Agriculture

Meeting.” Burlington Free Press and

Times, February 1, 1890, 4.

Web:

Vermont Landscape Change Program, http://www.uvm.edu/landscape/menu.php

(search Franklin).

Wikipedia, “Central Vermont Rail Way,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Central_Vermont_Railway.

USDA. “Franklin County Vermont, 2007 Census of

Agriculture.” http://www.agcensus.usda.gov/Publications/2007/Online_Highlights/County_Profiles/Vermont/cp50011.pdf

[1] Zadock Thompson, Gazetteer of the State of Vermont: Contains a Brief General View of the State: A Historical and Topographical Description (Montpelier: E. R. Walton, 1824) 306.

[2] Franklin County Agricultural Society: Record

Book 1844-1889. Manuscript. University of Vermont Special

Collections.

[3] Abby Hemenway, ed, The Vermont

Historical Gazetteer: a Magazine,

Embracing a History of Each Town, Civil, Ecclesiastical, Biographical and Military,

Volume 2. (Burlington, VT: Miss A.

M. Hemenway, 1871), 217-219.[4]

US Bureau of Census. Productions of Agricultural in the Town of

Franklin, Franklin County, Vermont. 1840.[5] Abby Hemenway, ed., The

Vermont Historical Gazetteer: a

Magazine, Embracing a History of Each Town, Civil, Ecclesiastical, Biographical

and Military, Volume 2. (Burlington,

VT: Miss A. M. Hemenway, 1871), 217-219.

[6] Zadock Thompson, Gazetteer of the State of Vermont: Contains a Brief General View of the State: A Historical and Topographical Description (Montpelier: E. R. Walton, 1824) 306.[7] Abby Hemenway, ed., The Vermont Historical Gazetteer: a Magazine, Embracing a History of Each Town,

Civil, Ecclesiastical, Biographical and Military, Volume 2. (Burlington, VT: Miss A. M. Hemenway, 1871),

217.[8] Abby Hemenway, ed., The Vermont Historical Gazetteer: a Magazine, Embracing a History of Each Town,

Civil, Ecclesiastical, Biographical and Military, Volume 2. (Burlington, VT: Miss A. M. Hemenway, 1871),

217.[9] Abby Hemenway, ed., The Vermont Historical Gazetteer: a Magazine, Embracing a History of Each Town,

Civil, Ecclesiastical, Biographical and Military, Volume 2. (Burlington, VT: Miss A. M. Hemenway, 1871),

217.

[10]

Agricultural Extension Service, University of Vermont. Agricultural

Trends in Franklin, Vermont: As a report on Project Number 665-12-3-56,

Conducted Under the Auspices of the Works Project Administration. (Burlington, VT: Agricultural Extension Service, University of Vermont, and State

Agricultural College, 1941), 2.[11] Abby Hemenway, ed., The Vermont Historical Gazetteer:

The Vermont Historical Gazetteer: a Magazine, Embracing a History of Each Town,

Civil, Ecclesiastical, Biographical and Military, Volume 2. (Burlington,

VT: Miss A. M. Hemenway, 1871), 219.[12] Abby Hemenway, ed., The Vermont Historical Gazetteer: a Magazine, Embracing a History of Each Town,

Civil, Ecclesiastical, Biographical and Military, Volume 2. (Burlington, VT: Miss A. M. Hemenway, 1871),

219.[13]Zadock Thompson. Gazetteer of the State of Vermont. (Montpelier: E.P. Walton, 1824), 306.[14]

Abby Hemenway, ed., The Vermont Historical Gazetteer: a Magazine, Embracing a History of Each Town,

Civil, Ecclesiastical, Biographical and Military, Volume 2. (Burlington,

VT: Miss A. M. Hemenway, 1871), 228.[15] Abby Hemenway, ed., The Vermont Historical Gazetteer: a Magazine, Embracing a History of Each Town,

Civil, Ecclesiastical, Biographical and Military, Volume 2. (Burlington, VT: Miss A. M. Hemenway, 1871),

228.[16] Abby Hemenway, ed., The Vermont Historical Gazetteer: a Magazine, Embracing a History of Each Town,

Civil, Ecclesiastical, Biographical and Military, Volume 2. (Burlington, VT: Miss A. M. Hemenway, 1871),

228.[17]Town of Franklin, Vital Records and Cattle Marks, 1791-1854. Franklin, VT: On File with the Town Clerk.[18]

Howard S. Russell, A Long, Deep Furrow: Three Centuries of Farming in New England. (Hanover,

NH: University Press of New England, 1976), 354.[19] Howard S. Russell, A Long, Deep Furrow: Three Centuries of Farming in New England. (Hanover,

NH: University Press of New England, 1976), 354.[20]

Wikipedia, “Central Vermont Rail Way,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Central_Vermont_Railway.[21] Howard S. Russell, A Long, Deep Furrow: Three Centuries of Farming in New England. (Hanover,

NH: University Press of New England, 1976), 354.

[22]

Agricultural Extension Service, University of Vermont. Agricultural

Trends in Franklin, Vermont: As a report on Project Number 665-12-3-56,

Conducted Under the Auspices of the Works Project Administration. (Burlington, VT: Agricultural Extension Service, University of Vermont, and State

Agricultural College, 1941), 4-5.

[23]

US Bureau of Census. Productions of Agricultural in the Town of

Franklin, Franklin County, Vermont. 1840, 1850,1860,1870,1880.

[24] US

Bureau of Census. Productions of Agricultural in the Town of Franklin, Franklin County,

Vermont. 1840, 1850,1860,1870,1880.

Also used: Agricultural Extension Service, University of Vermont. Agricultural

Trends in Franklin, Vermont: As a report on Project Number 665-12-3-56,

Conducted Under the Auspices of the Works Project Administration. (Burlington, VT: Agricultural Extension Service, University of Vermont, and State

Agricultural College, 1941), 2.

[25] Howard S. Russell, A Long, Deep Furrow: Three Centuries of Farming in New England. (Hanover,

NH: University Press of New England, 1976), 352.

[26] US

Bureau of Census. Productions of Agricultural in the Town of Franklin, Franklin County,

Vermont. 1840, 1850,1860,1870,1880.

Also used: Agricultural Extension Service, University of Vermont. Agricultural

Trends in Franklin, Vermont: As a report on Project Number 665-12-3-56,

Conducted Under the Auspices of the Works Project Administration. (Burlington, VT: Agricultural Extension Service, University of Vermont, and State

Agricultural College, 1941), 2.

[27]Howard S. Russell, A Long, Deep Furrow: Three Centuries of Farming in New England. (Hanover,

NH: University Press of New England, 1976), 356.

[28] Thomas Visser, Field Guide to New England Barns

and Farm Buildings. (Lebanon, NH:

University Press of New England, 1997), 85.

29] Agricultural Extension Service,

University of Vermont. Agricultural Trends in Franklin, Vermont: As

a report on Project Number 665-12-3-56, Conducted Under the Auspices of the

Works Project Administration. (Burlington,

VT: Agricultural Extension Service,

University of Vermont, and State Agricultural College, 1941), 6-7.[30] UVM and State Agricultural College,

ed. Farm Census for the State of Vermont

Based on the Bureau of Census Unpublished Data, January 1, 1945. (Burlington, VT: UVM and State

Agricultural College Cooperative Extension Service, 1946),Table 5.

[31] Thomas Visser, Field Guide to New England Barns and Farm Buildings. (Lebanon, NH: University Press of New

England, 1997), 76-91.[32] “ Farmers at Franklin: Close of the

Board of Agriculture Meeting.”

Burlington Free Press and Times, February 1, 1890, 4.[33]E.H. Jenkins, ed., “USDA Bulletin: A Compilation of Analysis of

American Feeding Stuffs.” Washington:

Government Printing Office, 1892.

[34]

Farmers at Franklin: Close of the Board of Agriculture Meeting.” Burlington Free Press and Times, February 1,

1890, 4.[35]

USDA. “Franklin County Vermont, 2007

Census of Agriculture.” http://www.agcensus.usda.gov/Publications/2007/Full_Report/

36] US

Bureau of Census. Productions of Agricultural in the Town of Franklin, Franklin County,

Vermont. 1840, 1850.

[37] Abby Hemenway, ed., The Vermont Historical Gazetteer:

a Magazine, Embracing a History of Each Town, Civil, Ecclesiastical,

Biographical and Military, Volume 2.

(Burlington, VT: Miss A. M. Hemenway, 1871), 219.

[38] Thomas Visser, Field Guide to New England Barns and Farm Buildings. (Lebanon, NH: University Press of New

England, 1997), 76-91.

|